Foreword to the French edition of The Machiavellian Moment

Item No. 12.

Le Moment Machiavélien

Ever since its publication in 1975, J. G. A. Pocock’s The Machiavellian Moment has been recognised as a masterpiece. It is undoubtedly among the most influential works of history published in the latter half of the 20th century, doing for intellectual history what E. P. Thompson did for social history with The Making of the English Working Class (1963). For the uninitiated reader, however, it is both a daunting undertaking and an overwhelming experience, constituting something like a rite of passage for the students who encounter its vast canvas and impressionistic style for the first time. For the more initiated, those who are already familiar with the book’s terrain, repeated visits are always generously rewarded, with surprising new insights to be found on pages that have already been read several times over. In this way, by its density and elevated difficulty, the book has been able to remain a continuous inspiration - a permanent port of return - for intellectual historians working within a broad range of contexts, especially in that period of Western history loosely defined as post-feudal and pre-industrial.

The wide scope and revisionist intent of Pocock’s argument was bound to involve him in controversies with many specialist historians; controversies which in many cases are still with us and which over the past half century have elicited quite a number of exercises in self-exegesis on the part of Pocock. Particularly controversial was the book’s final chapter on “The Americanization of Virtue” and his depiction of the American Revolution as the last great act of the Renaissance. This called forth a strong reaction among historians wedded to a view of the Revolution as the inauguration of the modern, as a liberal-capitalist event, whose protagonists could hardly be seen to share the ancient anxieties of a Baron de Montesquieu or a Lord Bolingbroke. The absence of John Locke from the narrative, moreover, was one of the most frequent points of criticism levied against him, despite the fact that his decision to exclude Locke and the natural law tradition more generally was presented by Pocock as simply a ‘tactical necessity’ at the time. As he wrote in 1975: ‘The historical context must be reconsidered without him before he can be fitted back in’ (TMM, 1975, p. 424).

By 1994, Pocock had become thoroughly exhausted by his involvement in American ideological debates. The final chapter had merely been ‘an afterthought’ and his intention to provoke had been ‘too successful for his own comfort.’ (see below, p. 5.) In a foreword written that year to accompany a French edition of the book, he announced his wish to depart from further ideological entanglements, remarking to his prospective French audience how strange it may seem ‘to European readers that a “republican” interpretation of the origins of the American republic should occasion controversy’. His foreword is essentially a long reading list designed to bring French readers up to date with subsequent developments in the world of scholarship, but aside from compensating for the book’s apparent “datedness”, which was Pocock’s main intention, the foreword actually reveals the extraordinary impact that it had exerted so far in so many areas of research, especially outside of the American arena, as well as demonstrating its continued relevance, as evidenced by the publication that same year of Biancamaria Fontana’s The Invention of the Modern Republic (1994).

- L. Andersen

-

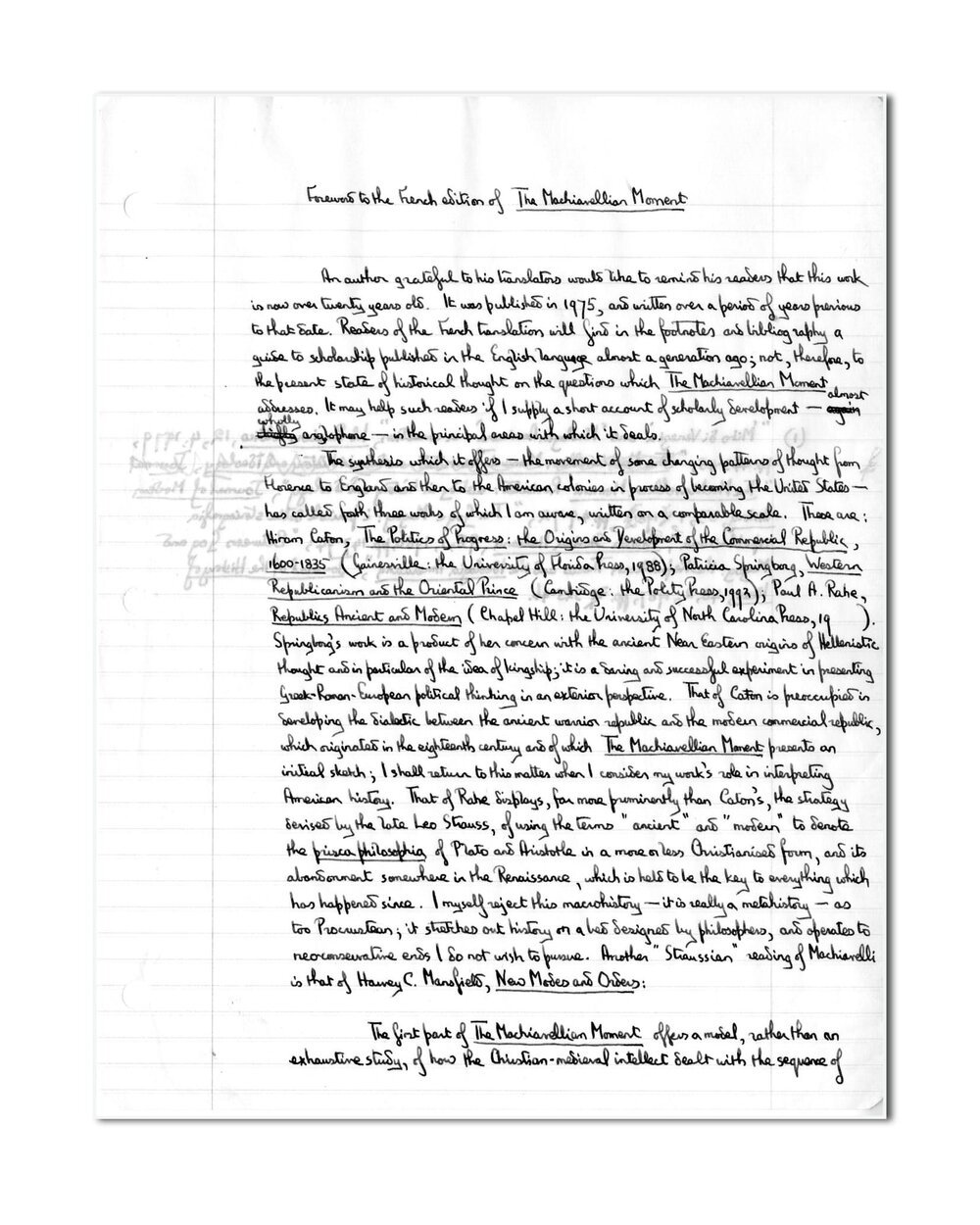

Foreword to the French edition of The Machiavellian Moment

An author grateful to his translators would like to remind his readers that this work is over twenty years old. It was published in 1975, and written over a period of years previous to that date. Readers of the French translation will find in the footnotes and bibliography a guide to scholarship published in the English language almost a generation ago; not, therefore, to the present state of historical thought on the questions which The Machiavellian Moment addresses. It may help such readers if I supply a short account of scholarly development - almost wholly anglophone - in the principal areas with which it deals. The synthesis which it offers - the movement of some changing patterns of thought from Florence to England and then to the America colonies in process of becoming the United States - has called forth three works of which I am aware, written on a comparable scale. These are Hiram Caton, The Politics of Progress: the Origins and Development of the Commercial Republic, 1600-1835 (Gainesville: the University of Florida Press, 1988); Patricia Springborg, Western Republicanism and the Oriental Prince (Cambridge: the Polity Press, 1992); Paul A. Rahe, Republics Ancient and Modern (Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 1992 ). Springborg’s work is a product of her concern with the ancient Near Eastern origins of Hellenistic thought and in particular of the idea of kingship; it is a daring and successful experiment in presenting Greek-Roman-European political thinking in an exterior perspective. That of Caton is preoccupied in developing the dialectic between ancient warrior republic and the modern commercial republic, which originated in the eighteenth century and which The Machiavellian Moment presents an initial sketch; I shall return to this matter when I consider my work’s role in interpreting American history. That of Rahe displays, far more prominently than Caton’s, the strategy devised by the late Leo Strauss, of using the terms “ancient” and “modern” to denote the prisca philosophia of Plato and Aristotle in a more or less Christianised form, and its abandonment somewhere in the Renaissance, which is held to be the key to everything which happened since. I myself reject this macro history - it is really a meta history - as too Procrustean; it stretches out history on a bed designed by philosophers, and operates to neoconservative ends I do not wish to pursue. Another “Straussian” reading of Machiavelli is that of Harvey C. Mansfield, New Modes and Orders:

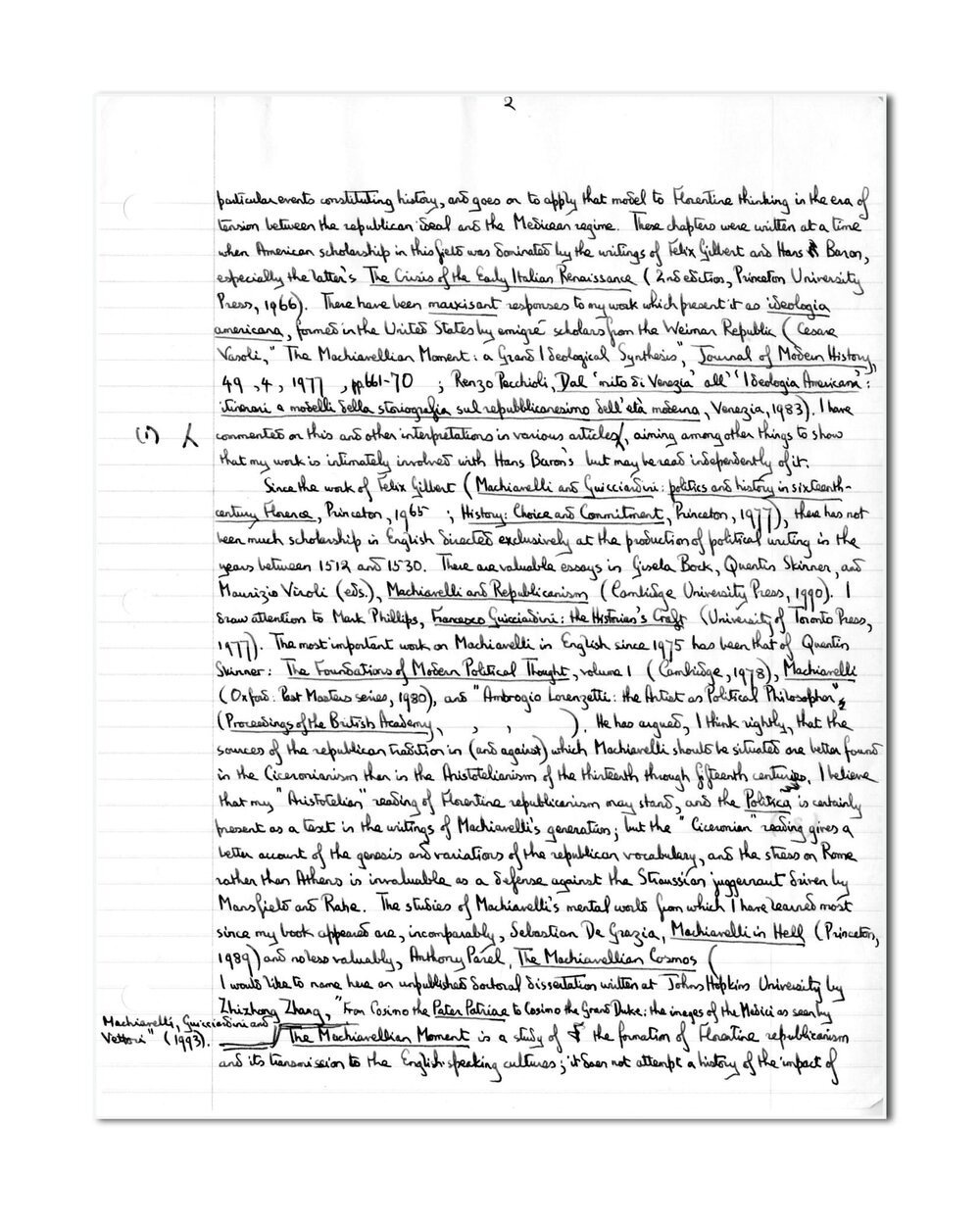

The first part of The Machiavellian Moment offers a model, rather than an exhaustive study, of how the Christian-medieval intellect dealt with the sequence of <2> particular events constituting history, and goes on to apply that model to Florentine thinking in the era of tension between the republican ideal and the Medicean regime. These chapters were written at a time when the American scholarship in this field was dominated by the writings of Felix Gilbert and Hans Baron, especially the latter’s The Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance (2nd edition, Princeton University, 1966). There have been marxisant responses to it which present as ideologia Americana, formed in the United States by emigré scholars from the Weimar Germany (Cesare Vasoli, “The Machiavellian Moment: a Grand Ideological Synthesis”, Journal of Modern History, 49, 4, 1977, pp. 661-70; Renzo Pecchioli, Dal 'Mito di Venezia’ all’'Ideologia Americana’: Itinerari e modelli della storiografia sul repubblicanesimo dell’età moderna, Venezia, 1983). I have commented on this and other interpretations in various articles,[1] aiming among other things to show that my work is intimately involved with Hans Baron’s but may be read independently of it.

Since the work of Felix Gilbert (Machiavelli and Guicciardini: politics and history in sixteenth century Florence, Princeton, 1965; History: Choice and Commitment, Princeton, 1977), there has not been much scholarship in English directed exclusively at the production of political writing in the years between 1512 and 1530. There are valuable essays in Gisela Bock, Quentin Skinner, and Maurizio Viroli (eds.), Machiavelli and Republicanism (Cambridge University Press, 1990). I draw attention to Mark Phillips, Francesco Guicciardini: the Historian’s Craft (University of Toronto Press, 1977). The most important work on Machiavelli in English since 1975 has been that of Quentin Skinner: The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, volume 1 (Cambridge, 1978), Machiavelli (Oxford: Past Masters series, 1980), and “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: the Artist as Political Philosopher” (Proceedings of the British Academy, 1986). He has argued, I think rightly, that the sources of the republican tradition in (and against) which Machiavelli should be situated are better found in the Ciceronianism than in the Aristotelianism of the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries, I believe that my “Aristotelian” reading for Florentine republicanism may stand, and the Politica is certainly present as a text in the writings of Machiavelli’s generation; but the “Ciceronian” reading gives a better account of the genesis and variations of the republican vocabulary, and the stress on Rome rather than Athens is invaluable as a defence against the Straussian juggernaut driven by Mansfield and Rahe. The studies of Machiavelli’s mental world from which I have learned most since my book appeared are, incomparably, Sebastian De Grazia, Machiavelli in Hell (Princeton, 1989) and no less valuable, Anthony Parel, The Machiavellian Cosmos (1992).

I would like to name here an unpublished doctoral dissertation written at Johns Hopkins University by Zhizhang Zhang, “From Cosimo the Pater Patriae to Cosimo the Grand Duke: the Images of the Medici as seen by Machiavelli, Guicciardini and Vettori” (1993).

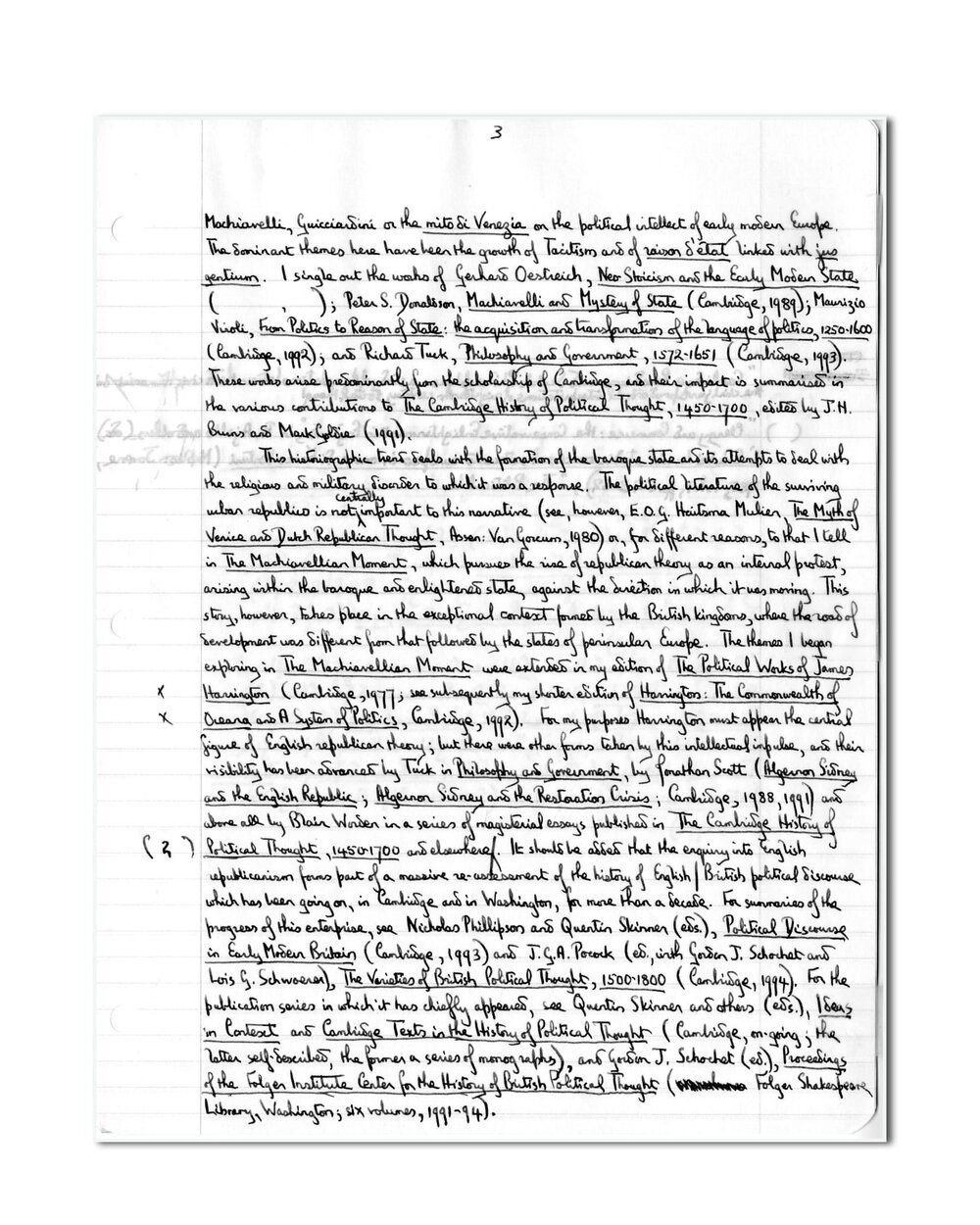

The Machiavellian Moment is a study of the formation of Florentine republicanism and its transmission to the English-speaking cultures; it does not attempt a history of the impact of <3> Machiavelli, Guicciardini or the mito di Venezia on the political intellect of early modern Europe. The dominant themes here have been the growth of Tacitism and of raison d’état linked with jus gentium. I single out the works of Gerhard Oestreich, Neostoicism and the Early Modern State (1982, ); Peter S. Donaldson, Machiavelli and Mystery of State (Cambridge, 1989); Maurizio Viroli From Politics to Reason of State: the acquisition and transformations of the language of politics, 1250-1600 (Cambridge, 1992); and Richard Tuck, Philosophy and Government, 1572-1651 (Cambridge, 1993). These works arise predominantly from the scholarship of Cambridge, and their impact is summarised in the various contributions to The Cambridge History of Political Thought, 1450-1700, edited by J. H. Burns and Mark Goldie (1991).

This historiographic trend deals with the formation of the baroque state and its attempts to deal with the religious and military disorder to which it was a response. The political literature of the surviving urban republics is not centrally important to this narrative (see, however, E. O. G. Haitsma Mulier, The Myth of Venice and Dutch Republican Thought, Assen: Van Gorcum, 1980), or, for different reasons, to that I tell in The Machiavellian Moment, which pursues the rise of republican theory as an internal protest, arising within the baroque and enlightened state, against the direction in which it was moving. This story, however, takes place in the exceptional context formed by the British kingdoms, where the road of development was different from that followed by the states of peninsular Europe. The themes I began exploring in The Machiavellian Moment were extended in my edition of Harrington: The Commonwealth of Oceana and A System of Politics, Cambridge, 1992). For my purposes Harrington must appear the central figure of English republican theory; but there were other forms taken by this intellectual impulse, and their risibility has been advanced by Tuck in Philosophy and Government, by Jonathan Scott (Algernon Sidney and the English Republic; Algernon Sidney and the Restoration Crisis; Cambridge, 1988, 1991) and above all by Blair Worden in a series of magisterial essays published in The Cambridge History of Political Thought, 1450-1700 and elsewhere.[2] It should be added that the enquiry into English republicanism forms part of a massive reassessment of the history of English/British political discourse which has been going on, in Cambridge and in Washington, for more than a decade. For summaries of the progress of this enterprise, see Nicholas Phillipson and Quentin Skinner (eds.), Political Discourse in Early Modern Britain (Cambridge, 1993) and J. G. A. Pocock (ed. With Gordon J. Schochet and Lois G. Schwoerer), The Varieties of British Political Thought (Cambridge, 1994). For the publication series in which it has chiefly appeared, see Quentin Skinner and others (eds.), Ideas in Context and Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought (Cambridge, on-going, the latter self-described, the former a series of monographs), and Gordon J. Schochet (ed.), Proceedings of the Folgen Institute Centre for the History of British Political Thought (Folgen Shakespeare Library, Washington, six volumes, 1991-94). <4>

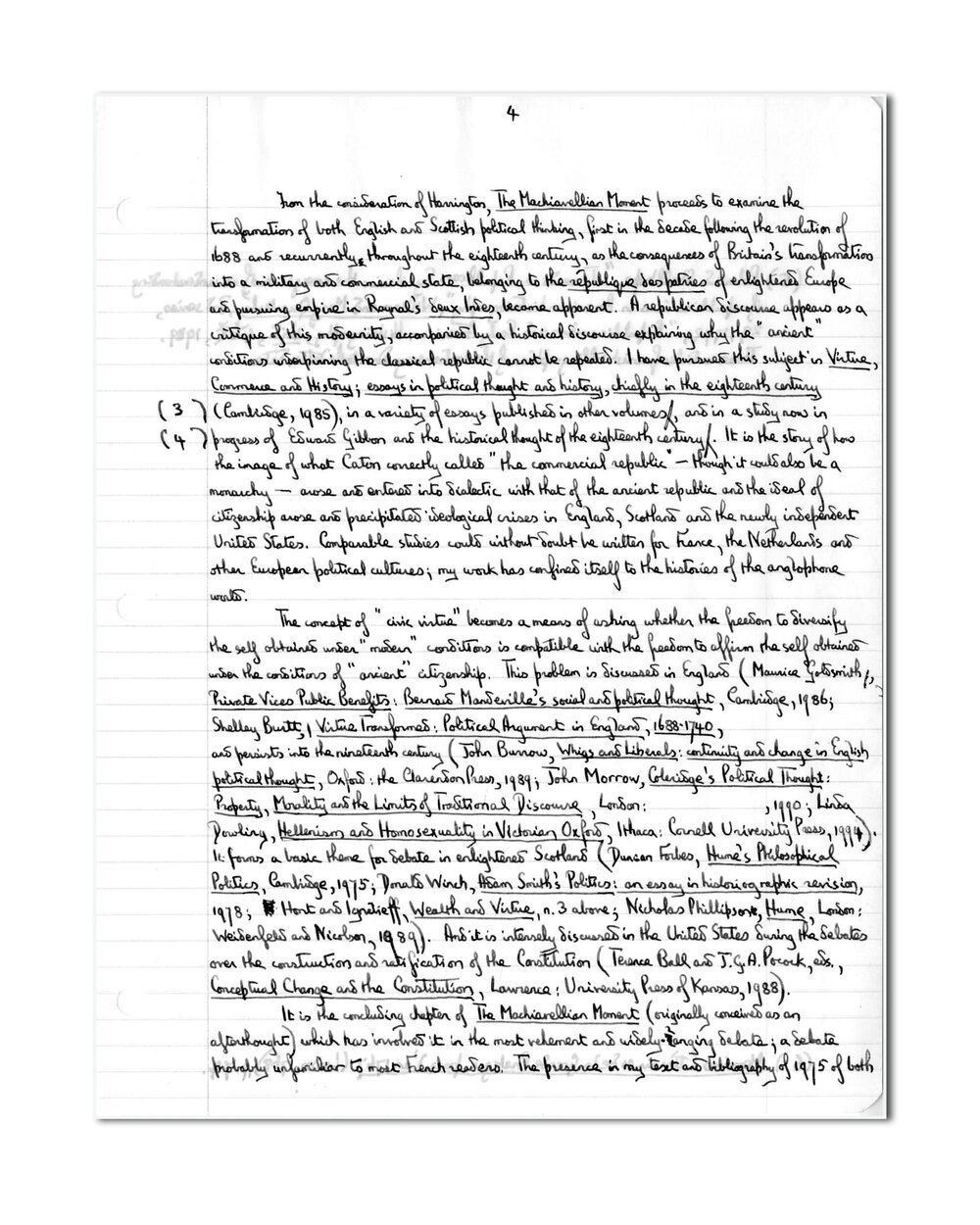

From the consideration of Harrington, The Machiavellian Moment proceeds to examine the transformation of both English and Scottish political thinking, first in the decade following the revolution of 1688 and secondly throughout the eighteenth century, as the consequences of Britain’s transformations into a military and commercial state, belonging to the républic des patries of enlightened Europe and pursuing empire in Raynal’s deux Indes, became apparent. A republican discourse appears as a critique of this modernity, accompanied by a historical discourse explaining why the “ancient” conditions underpinning the classical republic cannot be repeated. I have pursued this subject in Virtue, Commerce and History; essays in political thought and history, chiefly in the eighteenths century (Cambridge, 1985), in a variety of essays published in other volumes,[3] and in a study now in progress of Edward Gibbon and the historical thought of the eighteenth century.[4] It is to the study of how the image of what Caton correctly called “the commercial republic” - though it could also be a monarchy - arose and entered into dialectic with that of the ancient republic and the ideal of citizenship arose and precipitated ideological crises in England, Scotland and the newly independent United States. Comparable studies could without doubt be written for France, the Netherlands and other European political cultures; my work has confined itself to the histories of the anglophone world.

The concept of “civic virtue” becomes a means of asking whether the freedom to diversify the self obtained under “modern” conditions is compatible with the freedom to affirm the self obtained under condition of “ancient” citizenship. This problem is discussed in England (Maurice Goldsmith, Private Vices Public Benefits: Bernard Mandeville’s social and political thought, Cambridge, 1986; Shelley Burtt, Virtue Transformed: Political Argument in England, 1688-1740, and persists into the nineteenth century (John Burrow, Whigs and Liberals: continuity and change in English political thought, Oxford: the Clarendon Press, 1989; John Morrow, Coleridge’s Political Thought: Property, Morality and the Limits of Traditional Discourse, London: , 1990; Linda Dowling, Hellenism and Homosexuality in Victorian Oxford, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994). It forms a basic theme for the debate in enlightened Scotland (Duncan Forbes, Hume’s Philosophical Politics, Cambridge, 1975; Donald Winch, Adam Smith’s Politics: an essay in historiographic revision, 1978; Hont and Ignatieff, Wealth and Virtue, n. 3 above; Nicholas Phillipson, Hume, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989). And it is intensely discussed in the United States doing the debates over the construction and ratification of the Constitution (Terance Ball and J. G. A. Pocock, eds. Conceptual Change and the Constitution, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1988).

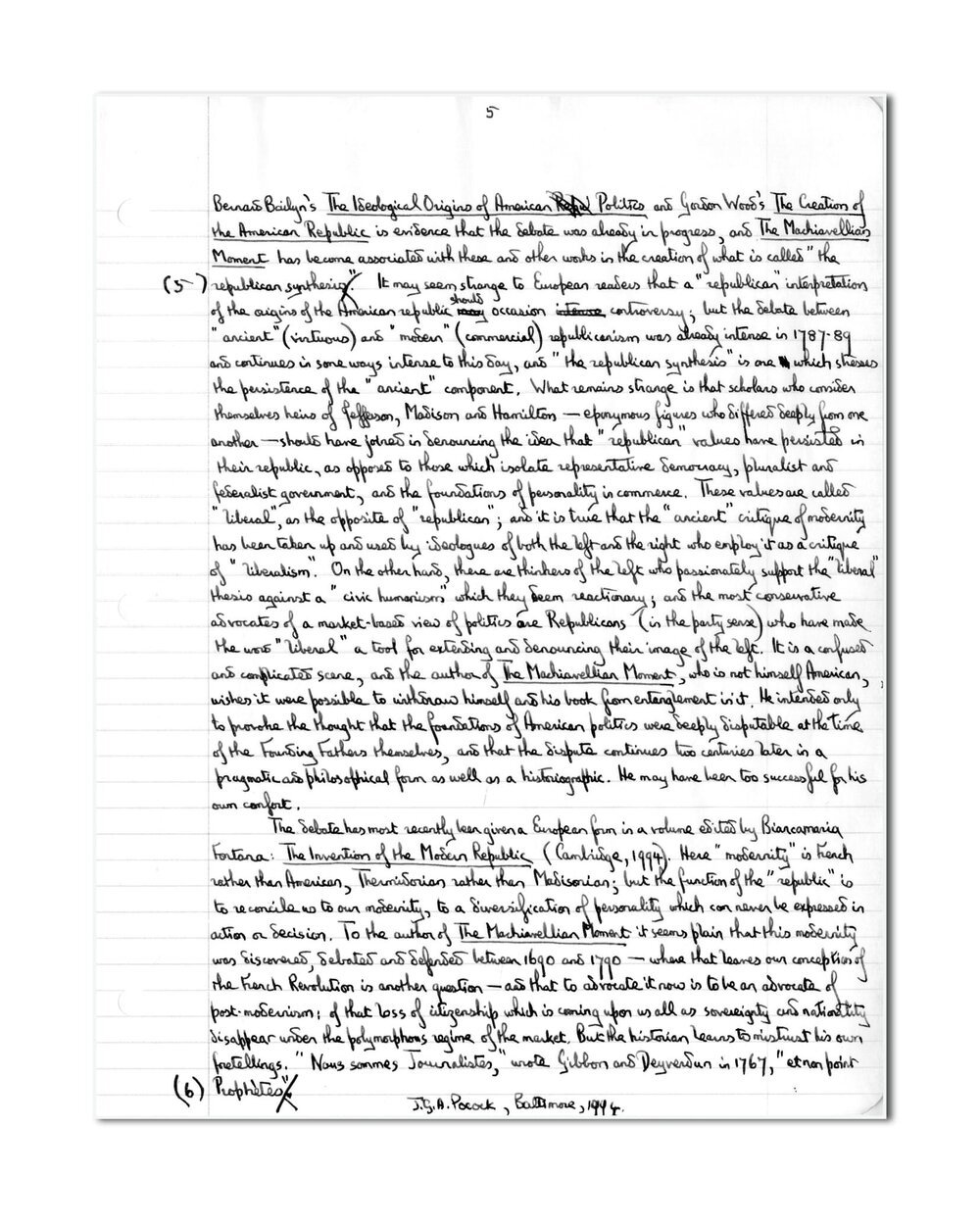

It is the concluding chapter of The Machiavellian Moment (originally conceived as an afterthought) which has involved it in the most vehement and widely-ranging debate; a debate probably unfamiliar to most French readers. The presence in my text and bibliography of 1975 of both <5> Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of American Politics [sic] and Gordon Wood’s, The Creation of the American Republic is evidence that the debate was already in progress, and The Machiavellian Moment has become associated with these and other works in the creation of what is called “The republican synthesis”.[5] It may seem strange to European readers that a “republican” interpretation of the origins of the American republic should occasion controversy; but the debate between “ancient” (virtuous) and “modern” (commercial) republicanism was already intense in 1787-89 and continues in some ways intense to this day, and “the republican synthesis” is one which stresses the “ancient” component. What remains strange is that scholars who consider themselves heirs of Jefferson, Madison and Hamilton - eponymous figures who differed deeply from one another - should have joined in denouncing the idea that “republican” values have persisted un their republic, as opposed to those which isolate representative democracy, pluralist and federalist government, and the foundations of personality in commerce. These values are called “liberal”, as the opposite of “republican”; and it is true that the “ancient” critique of modernity has been taken up and used by ideologues of both the left and right who employ it as a critique of “liberalism.” On the other hand, there are thinkers of the left who passionately support the “liberal” thesis against a “civic humanism” which they deem reactionary; and the most conservative advocates of a market-based society view of politics are Republicans (in the party sense) who have made the word “liberal” a tool for extending and denouncing their image of the left. It is a confused and complicated scene, and the author of The Machiavellian Moment, who is not himself American, wishes it were possible to withdraw himself and his book from entanglement in it. He intended only to provoke the thought that the foundations of American politics were deeply disputable at the time of the Founding Fathers themselves, and that the dispute continues two centuries later in a pragmatic and philosophical form as well as a historiographic. He may have been too successful for his own comfort.

The debate has most recently been given a European form in a volume edited by Biancamaria Fontana: The Invention of the Modern Republic (Cambridge, 1994). Here “modernity” is French rather than American, Thermidorian rather than Madisonian; but the function of the republic is to reconcile us to our modernity, to a diversification of personality which can never be expressed in action or decision. To the author of The Machiavellian Moment it seems plain that this modernity was discovered, debated and defended between 1690 and 1790 - where that leaves our conception of the French Revolution is another question - and that to advocate it now is to be an advocate of post-modernism: of that loss of citizenship which is coming upon us all as sovereignty and nationality disappear under the polymorphous regime of the market. But the historian lives to mistrust his own foretelling. “Nous sommes Journalistes”, wrote Gibbon and Deyverdun in 1767, “et non point Prophètes”.[6]

J. G. A. Pocock, Baltimore, 1994.

-

[1] “‘Mito di Venezia’ and ‘Ideologia Americana’: a conection “, Il Pensiero Politico, 12, 4, 1979, pp. 443-45; “The Machiavellian Moment Revisited: a study in history and ideology”, Journal of Modern History, 53, 1, 1981, pp. 49-72; “Tra Gog e Magog: I pericoli della storiografia repubblicana”, Rivista Storica Italiana, 98, 1, 1986, pp. 147-94; “Between Gog and Magog: the Republican Thesis and the Ideologia Americana”, Journal of the History of Ideas, 48, 2, 1987, pp. 325-46.

[2] [missing]

[3] “Cambridge Paradigms and Scott philosophers: a study of the relations between the civic humanist and the civil jurisprudential interpretations of eighteenth-century social thought”, in Istvan Hont and Michael Ignatieff (eds.), Wealth and Virtue: the shaping of political economy in the Scottish Enlightenment (Cambridge, 1983); “Clergy and Commerce: the Conservative Enlightenment in England”, in R. Ajello and others (eds.) L'eta dei lumi: Studi storici sul Settecento europeo in onore di Franco Venturi (Naples, Jovene, 1985); “The Significance of 1688: some reflections on Whig history,” in R. A. Beddard (ed.), The Revolutions of 1688: the Andrew Browing Lectures, 1988 (Oxford, the Clarendon press, 1990).

[4] “Between Clarendon and Hume: Gibbon as Civic Humanist and Philosophical Historian”, in Daedalus, 105, 3 and Glen Bowersock and John Clive (eds.), Edward Gibbon and the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977); “Edward Gibbon in History; Aspects of the Text in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”, in The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, vol. xi (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990).

[5] Robert S. Shallop, “Towards a Republican Synthesis: the emergence of an understanding of republicanism in American historiography”, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 29, 1972; “Republicanism and Early American Historiography”, ibid. 46, 1989. These articles furnish bibliographies of the controversy down to the latter date.

[6] Memoires Littèraires de la Grande Bretagne pour l’an 1767 (London, 1768), p. 74.