The Winch-Forbes Exchange

Item No. 7.

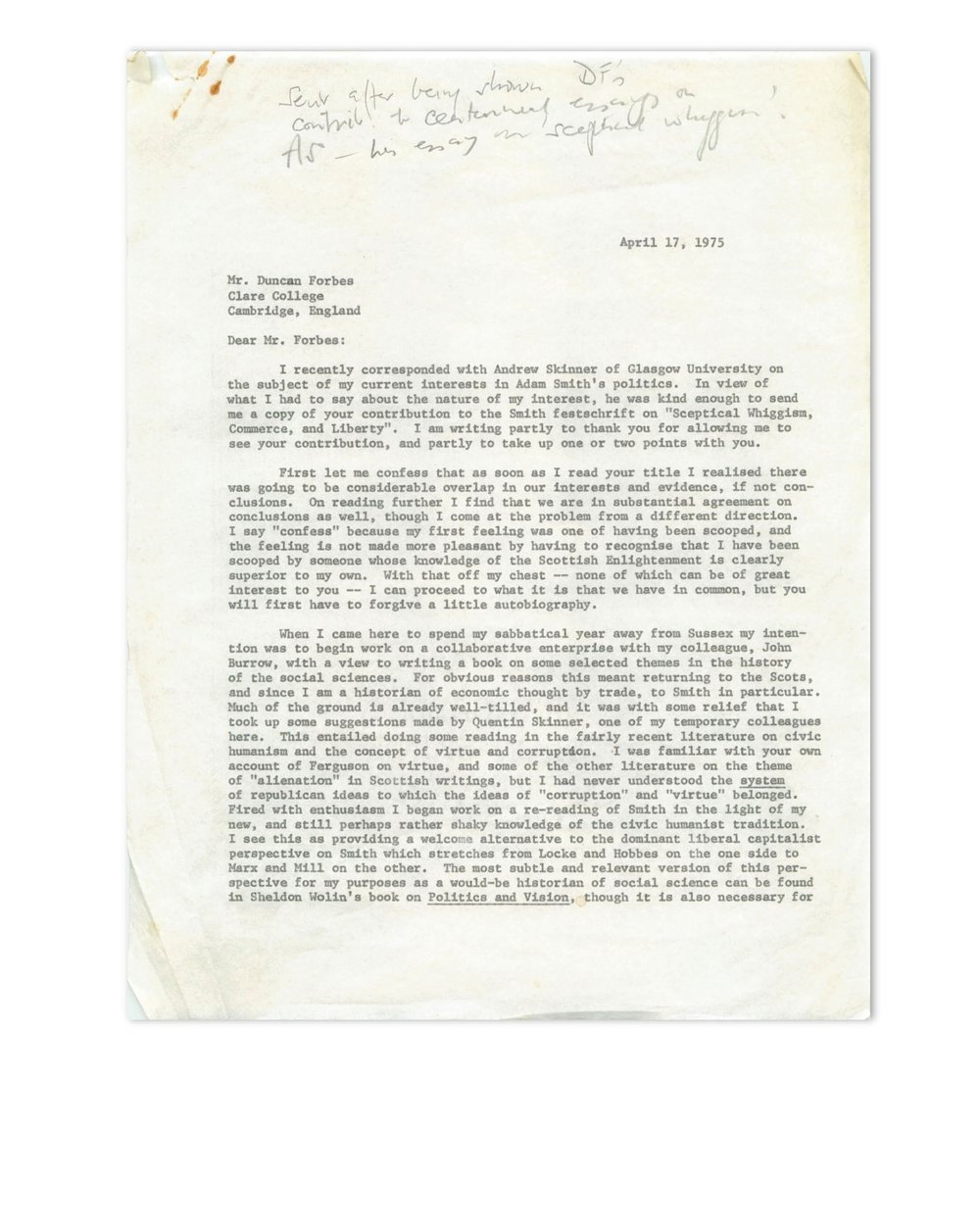

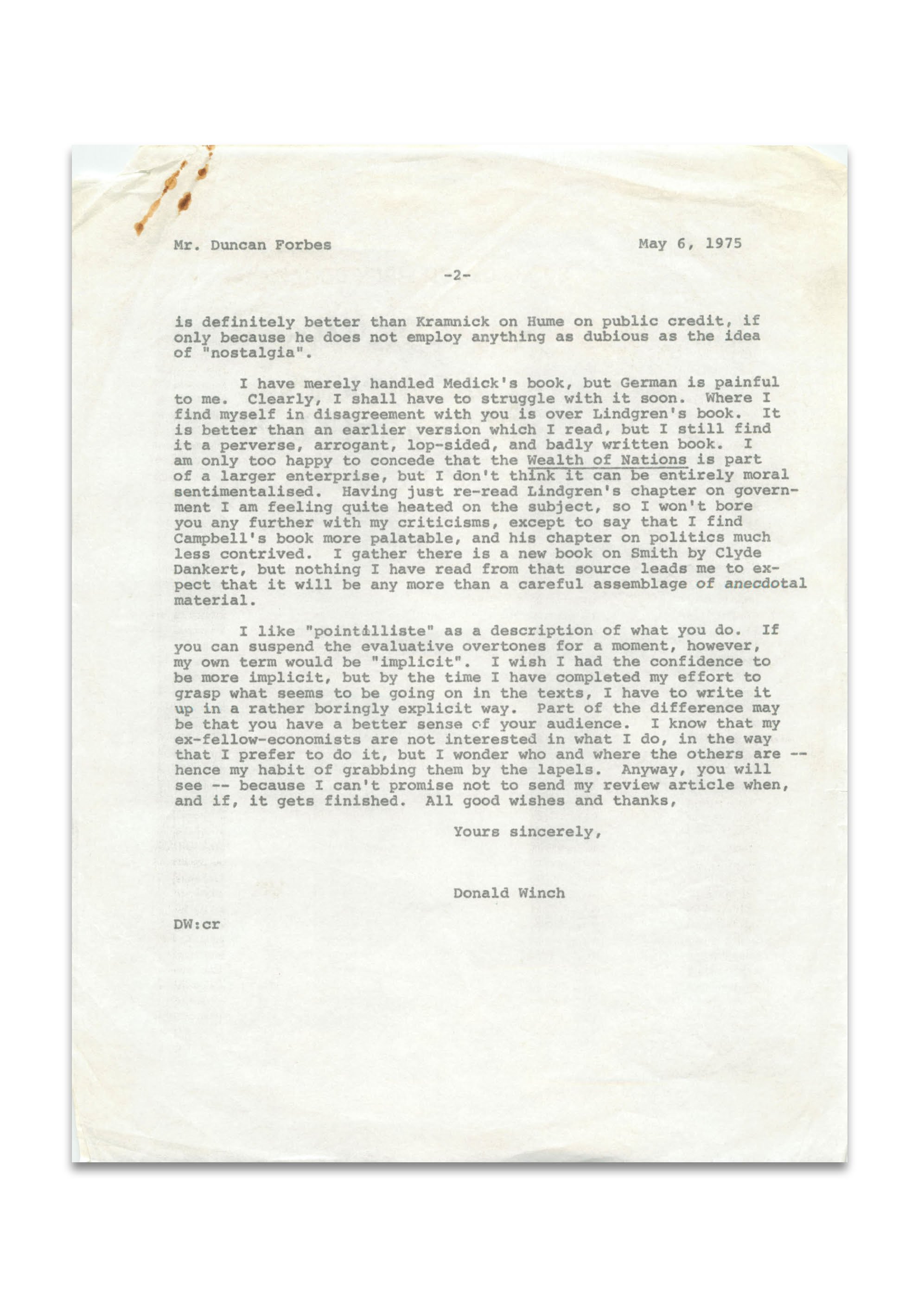

Donald Winch

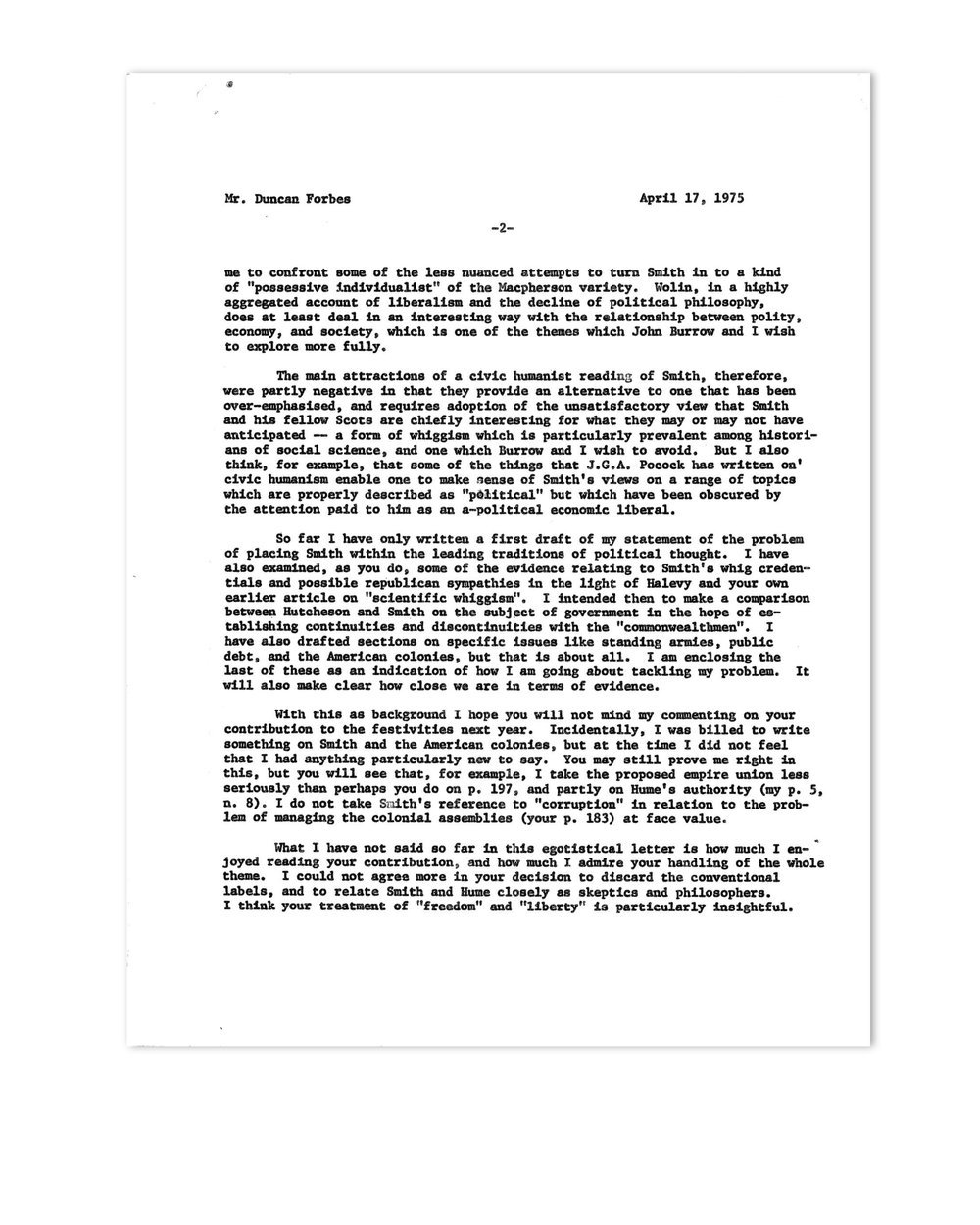

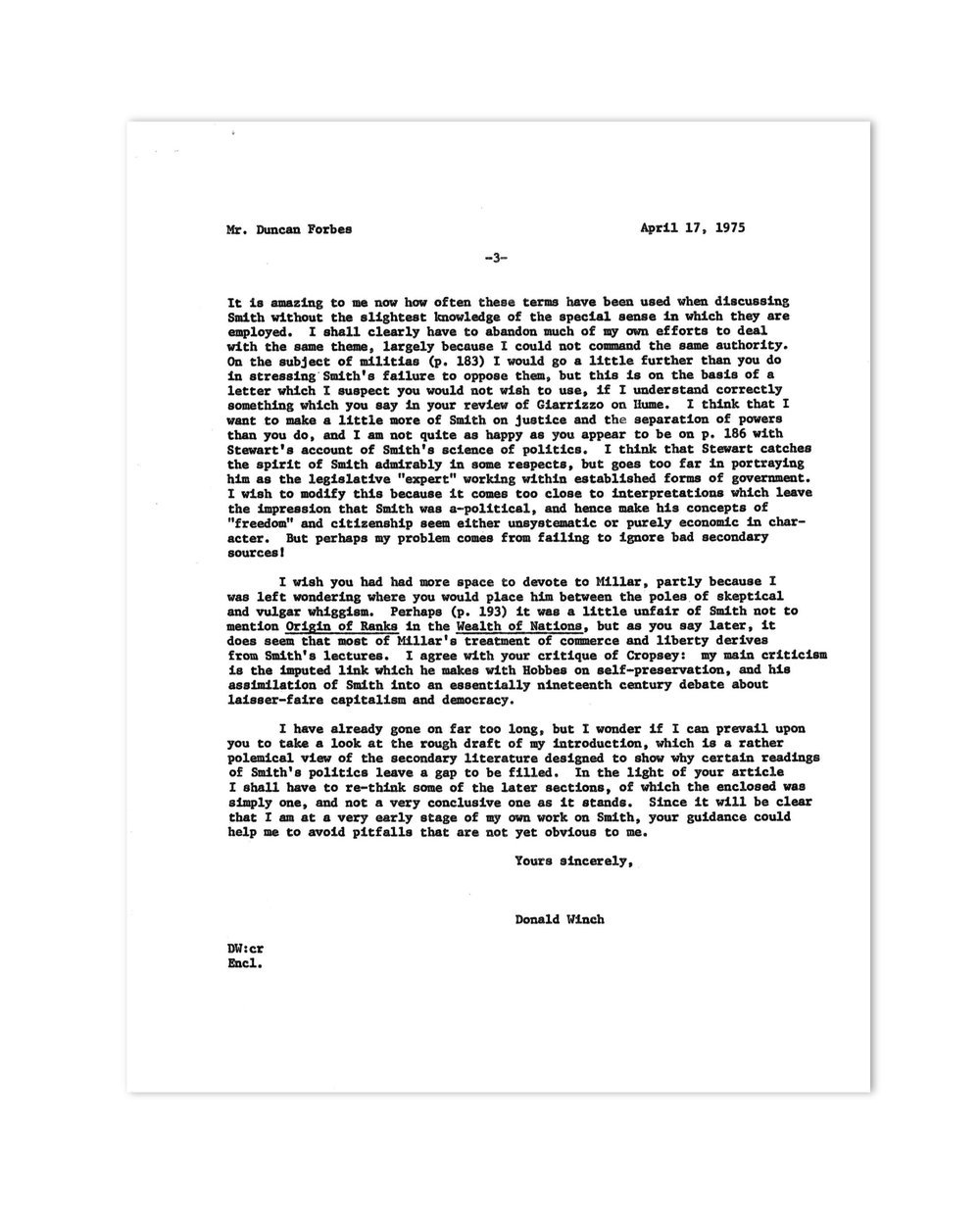

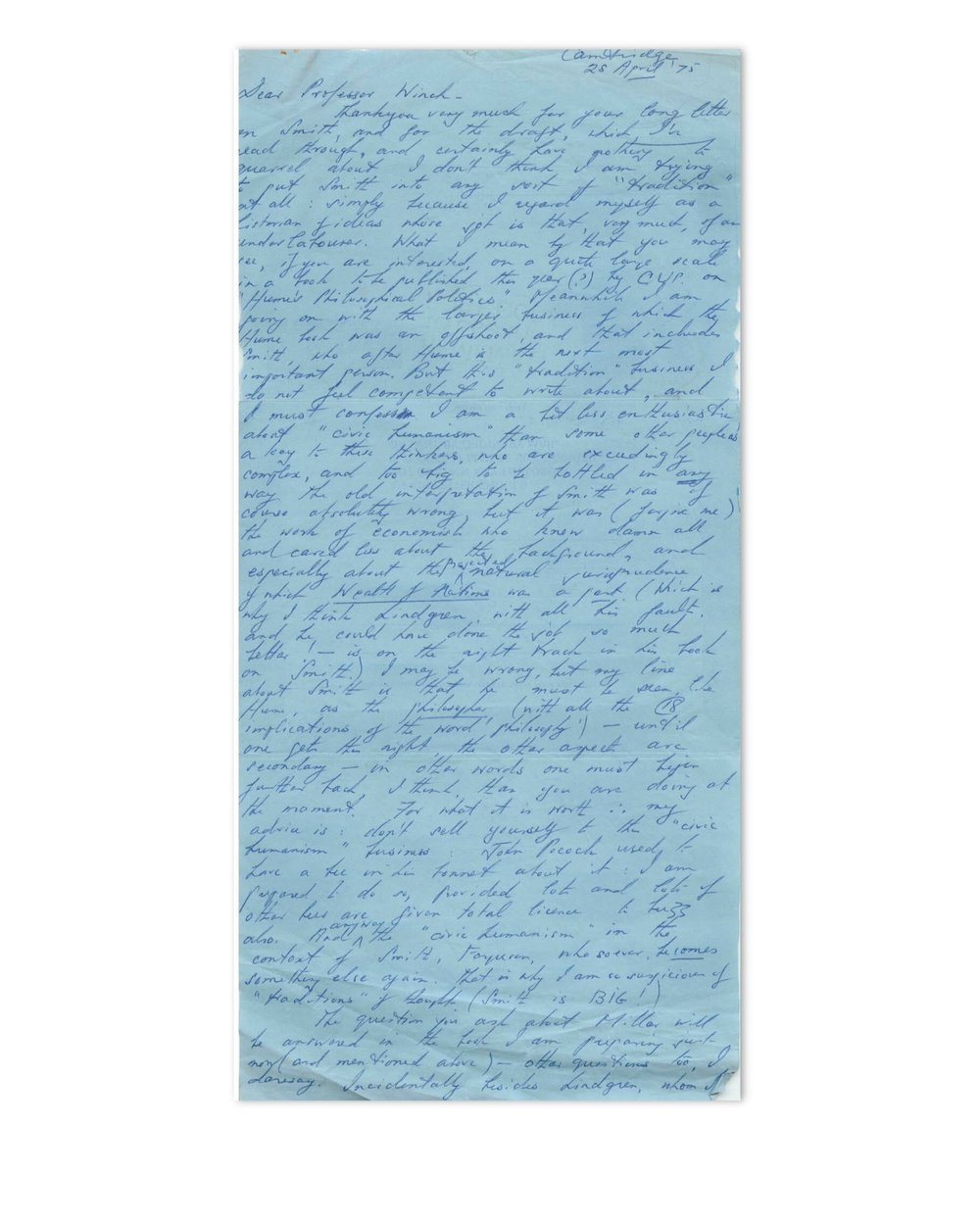

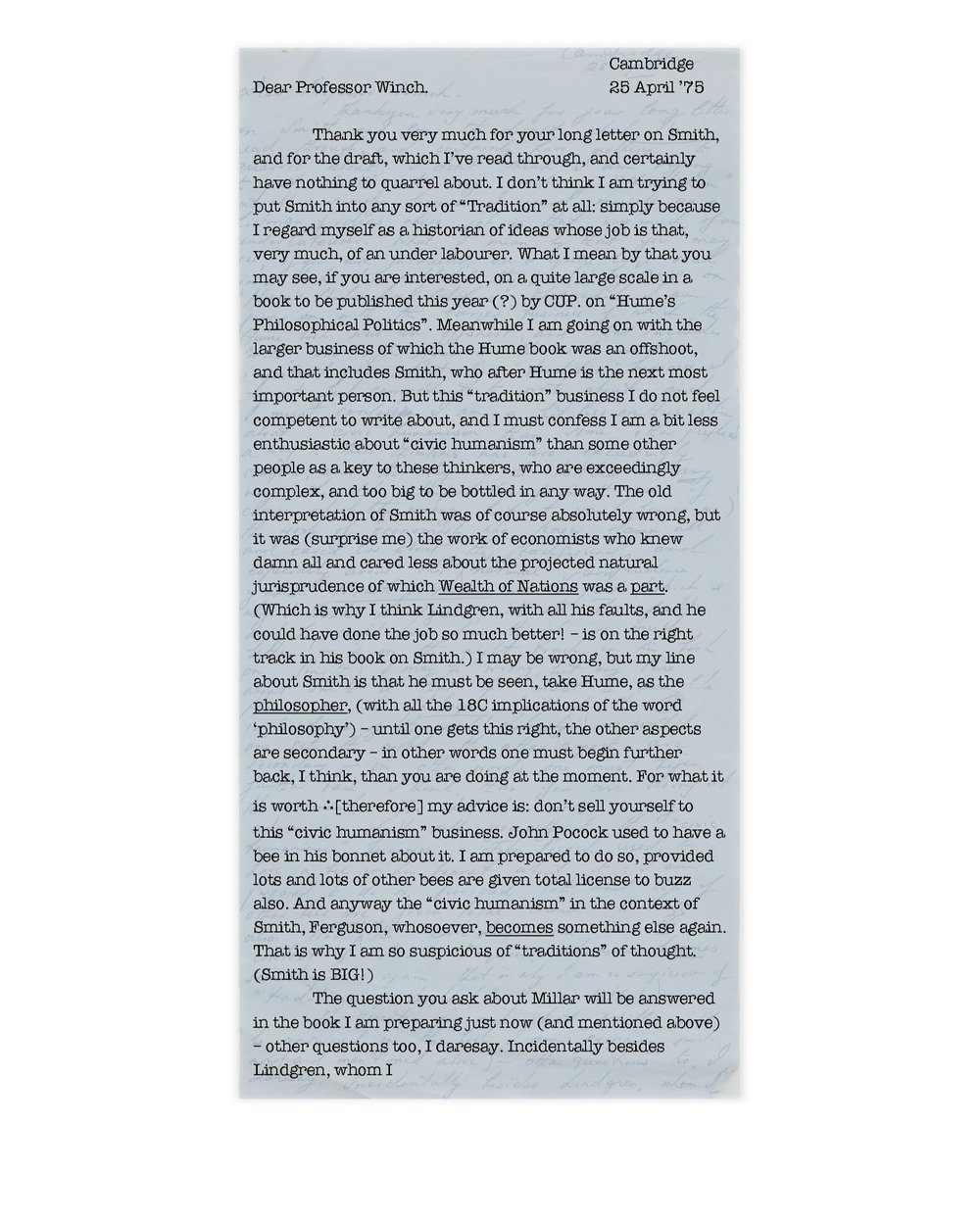

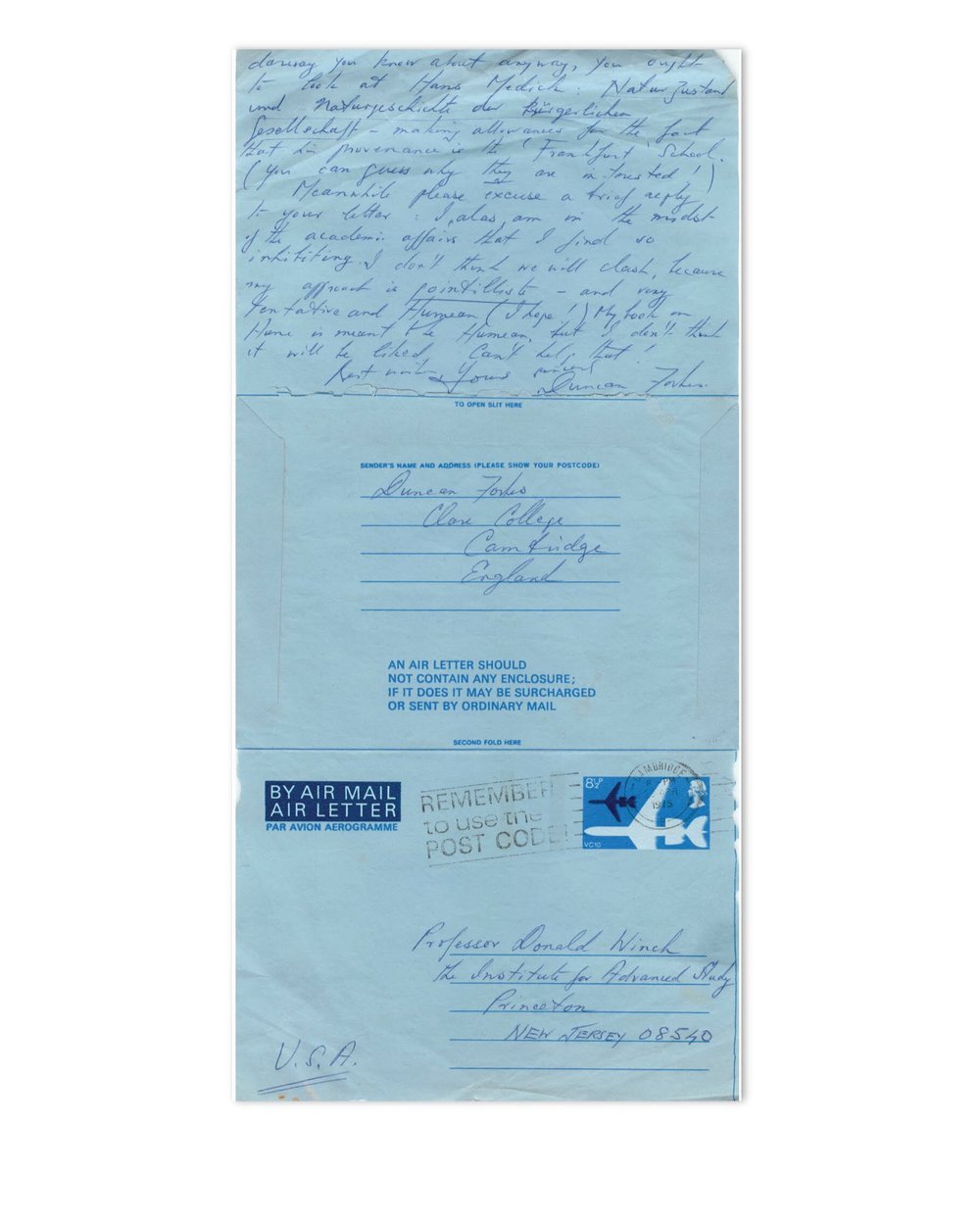

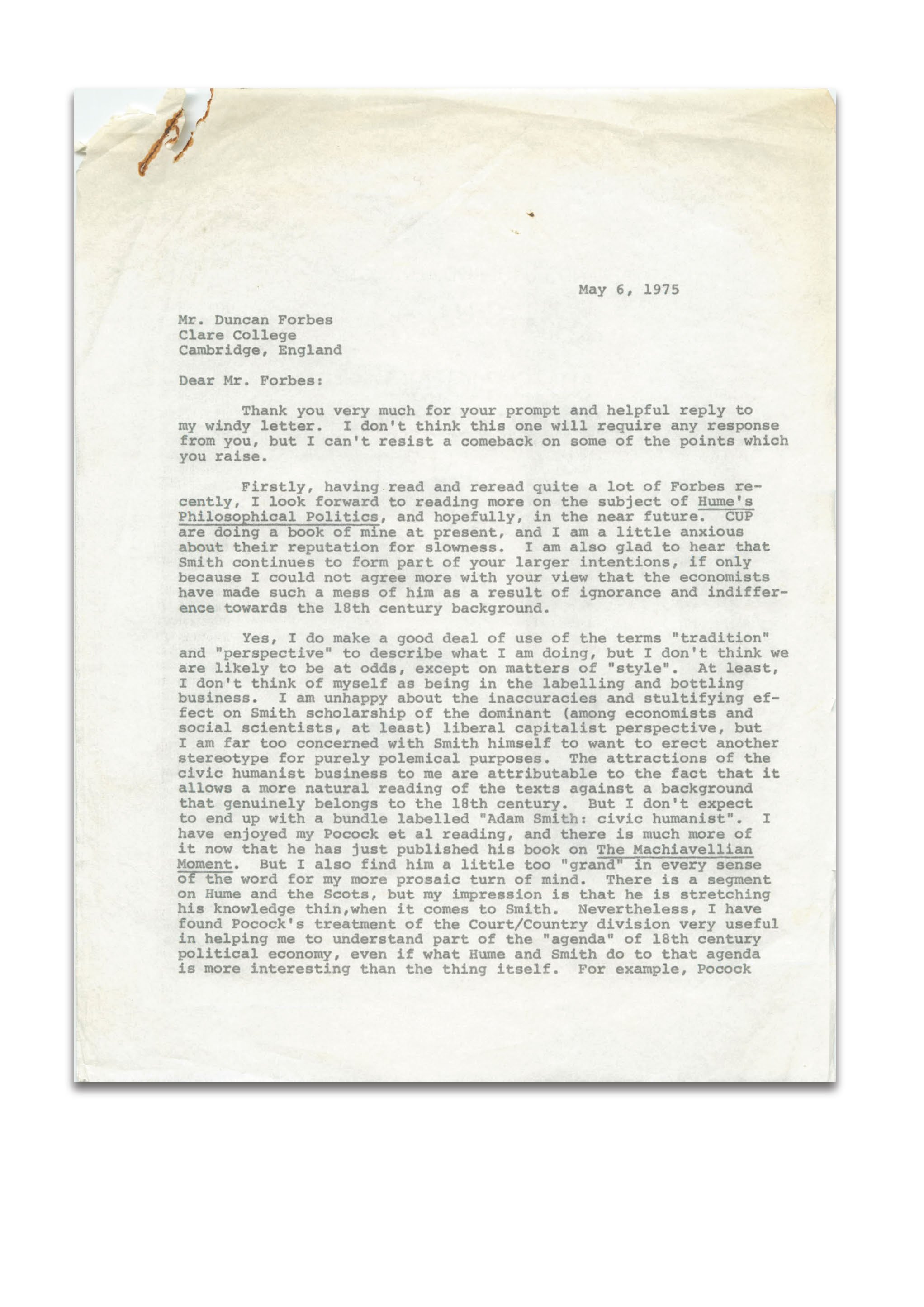

Donald Winch (1935- 2017) at the time of writing these letters was Professor of the History of Economic Thought at the University of Sussex. He had completed his PhD at Princeton under the guidance of the leading authority on the history of economics Jacob Viner. After teaching for a year at Berkeley, Winch was appointed to a lectureship in economics at Edinburgh before, in 1963, moving to the then new University of Sussex. Winch became Dean of the School of Social Sciences from 1968 to 1974 and then took a sabbatical at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. Having worked on 19th and 20th century economic thought and policy, Winch was turning his attention to Adam Smith. As he explains, Winch’s initial approach to Smith was heavily influenced by Quentin Skinner, a fellow visiting colleague at Princeton at the time. Skinner had recommended that Winch look into the history of civic humanism in relation to Smith, which meant engagement with the work of J. G. A. Pocock, who was just publishing The Machiavellian Moment (1975).

Winch was advised to contact Duncan Forbes by another historian of economic thought and Smith authority, Andrew Skinner of the University of Glasgow. Forbes, a fellow of Clare College Cambridge, had been teaching a famous special subject course on the Scottish Enlightenment and published his pathbreaking Hume’s Philosophical Politics in 1975. This book emphasised Hume’s debt to the tradition of natural jurisprudence. Andrew Skinner had shown Winch Forbes’s essay on ‘Sceptical Whiggism, Commerce and Liberty’, destined for the book Skinner edited with Thomas Wilson, Essays on Adam Smith (Oxford University Press, 1976). Winch had written the introduction to what became Adam Smith’s Politics (1978), intended to refute Marxist and Liberal association of Smith with laissez-faire economics. Reconstructing Smith’s politics, Winch was interested in Forbes’ opinion, not least because there appeared to be so much overlap in their research. The resulting exchange of letters is singularly revealing of leading projects in intellectual history in the mid-1970s and especially concerning the reception of John Pocock’s interpretation of civic humanism.

Note: The originals of these letters can be found in the Donald Winch papers at the University of Sussex with copies in the Duncan Forbes’ papers at Jesus College, Cambridge. The letters are reproduced by permission of Stefan Collini, Executor of Donald Winch's estate.