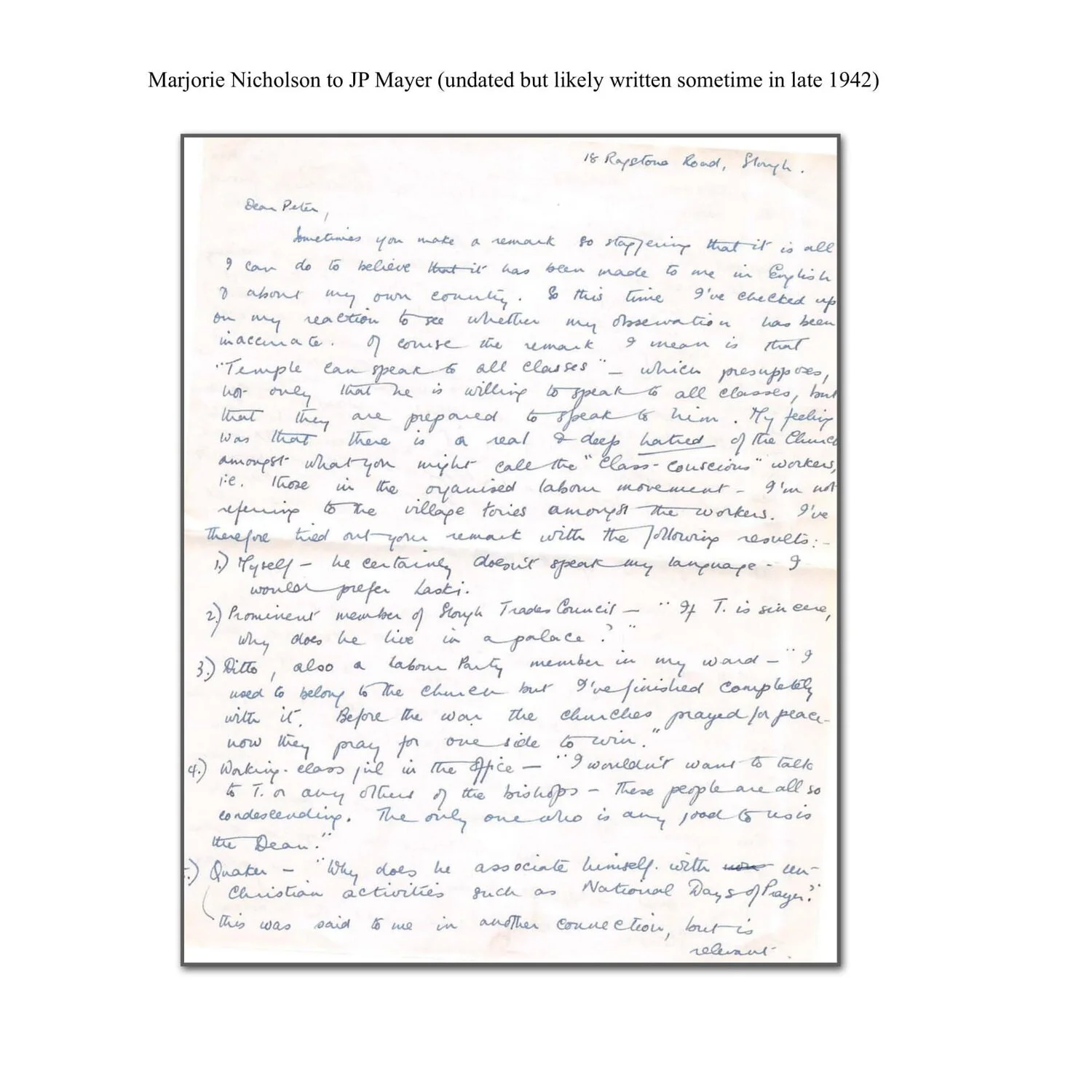

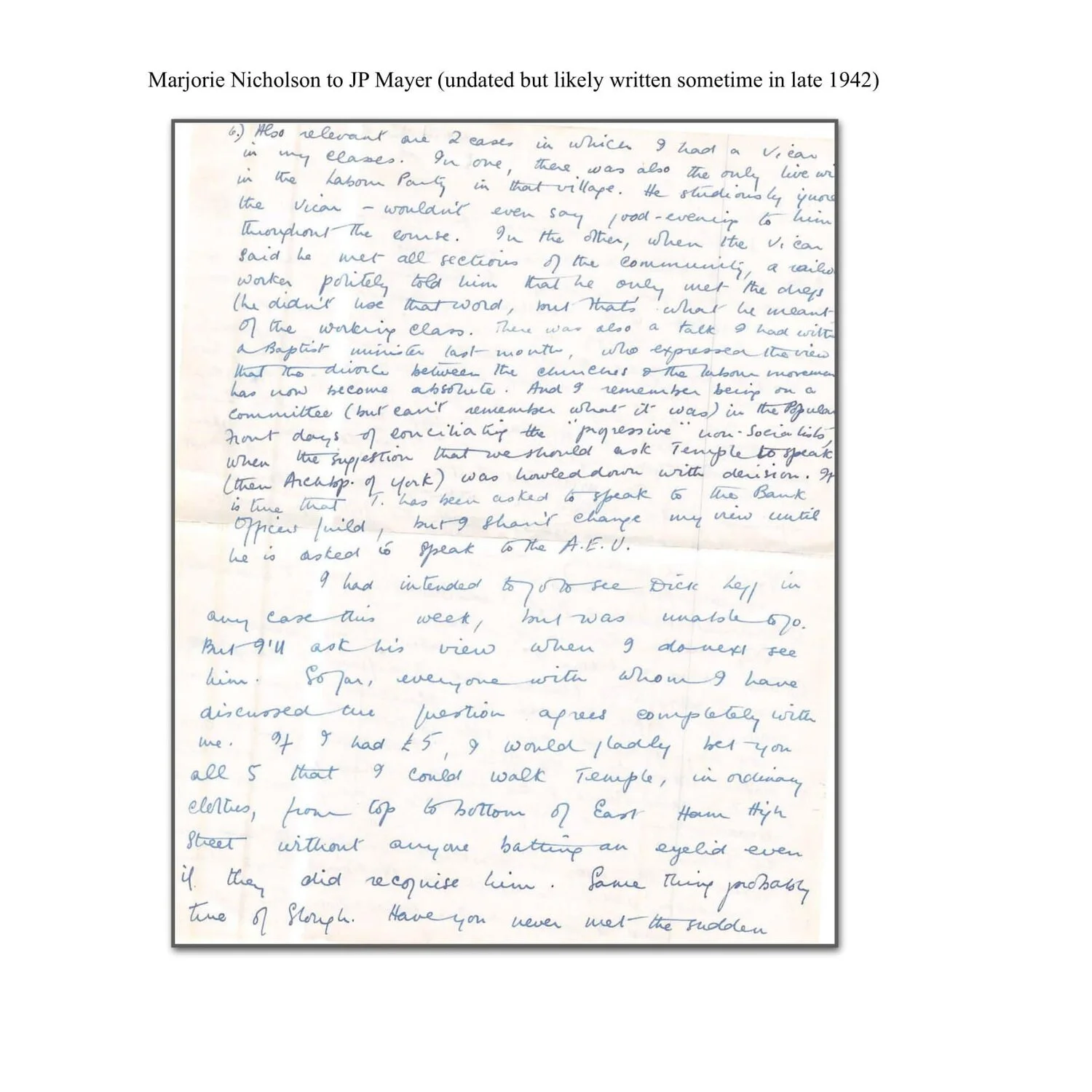

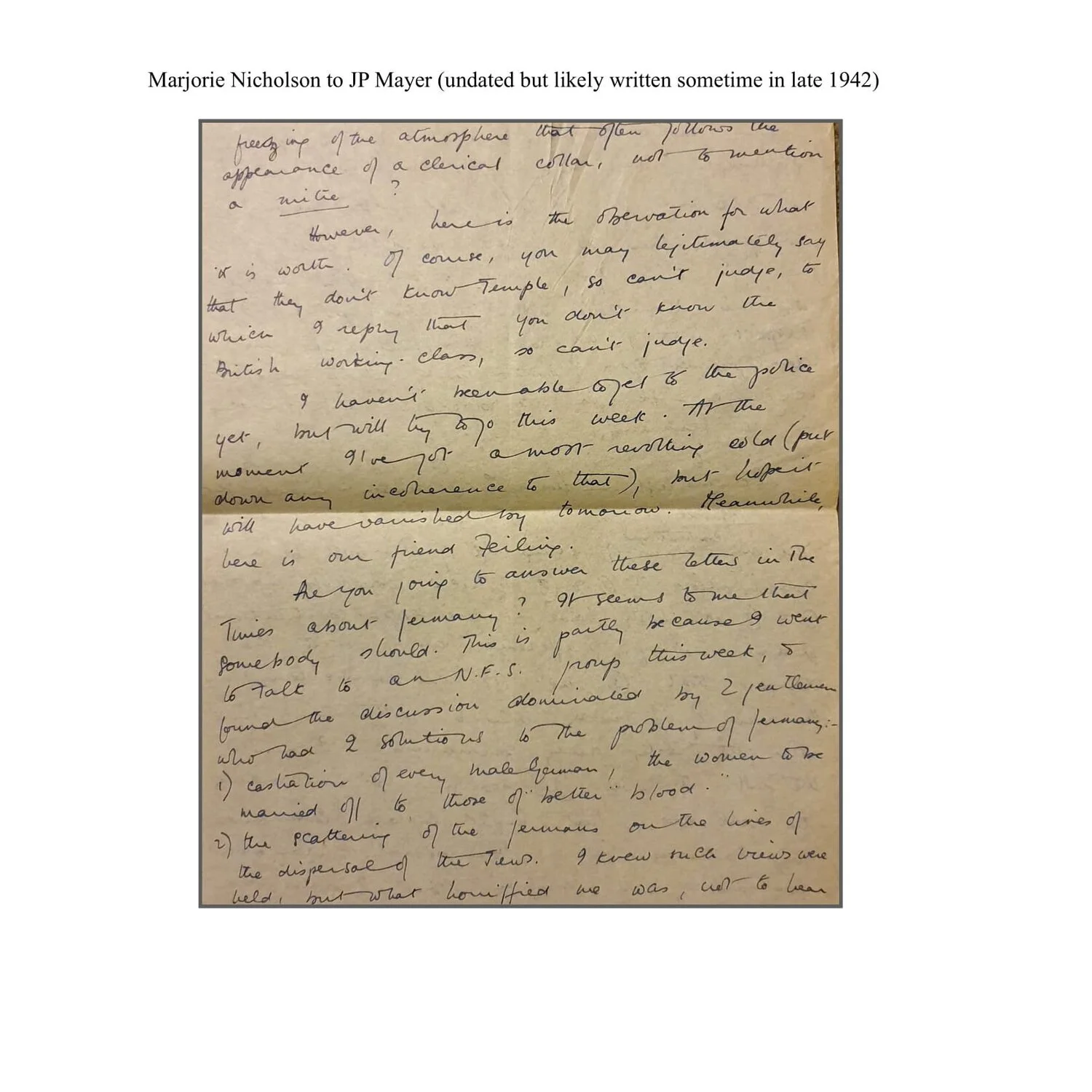

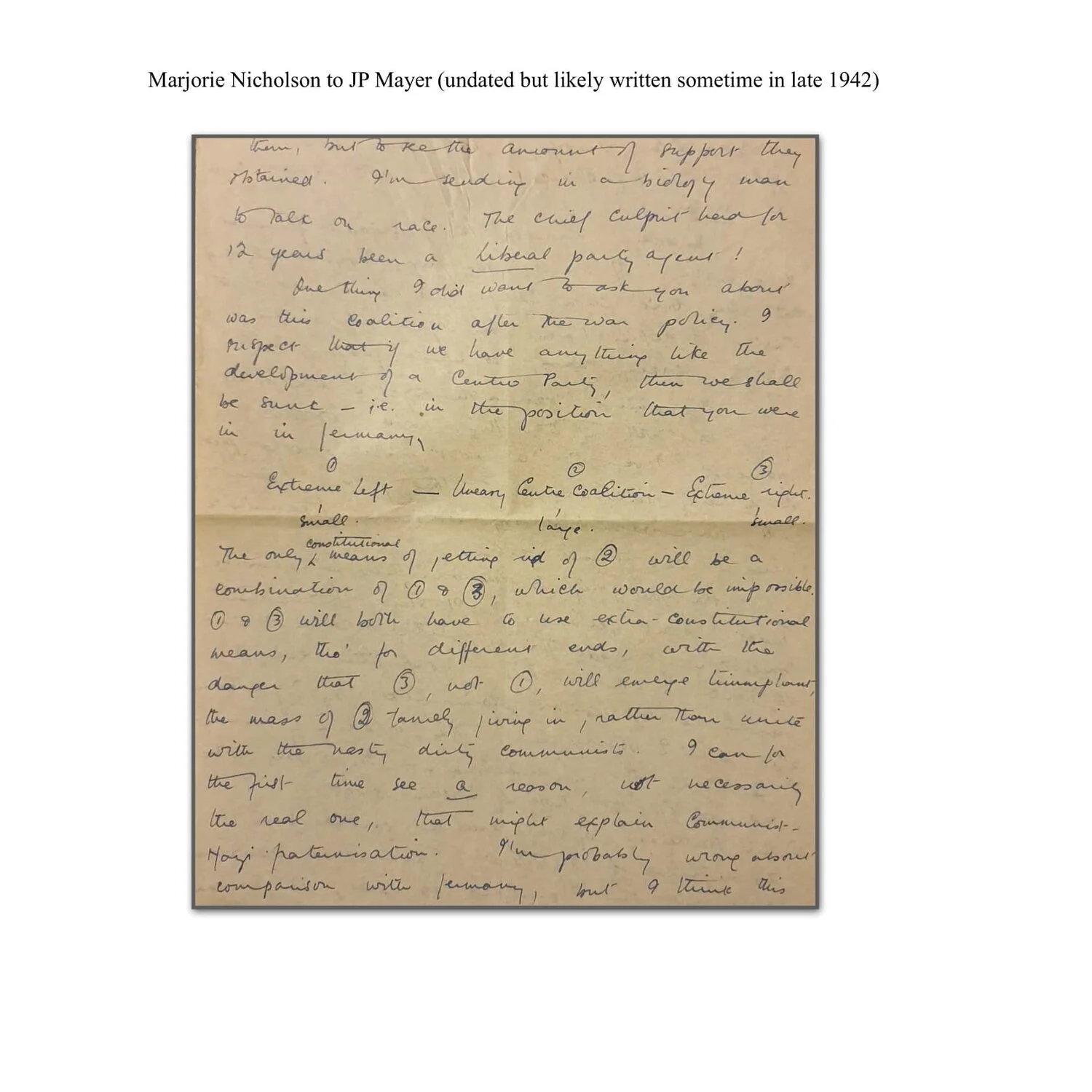

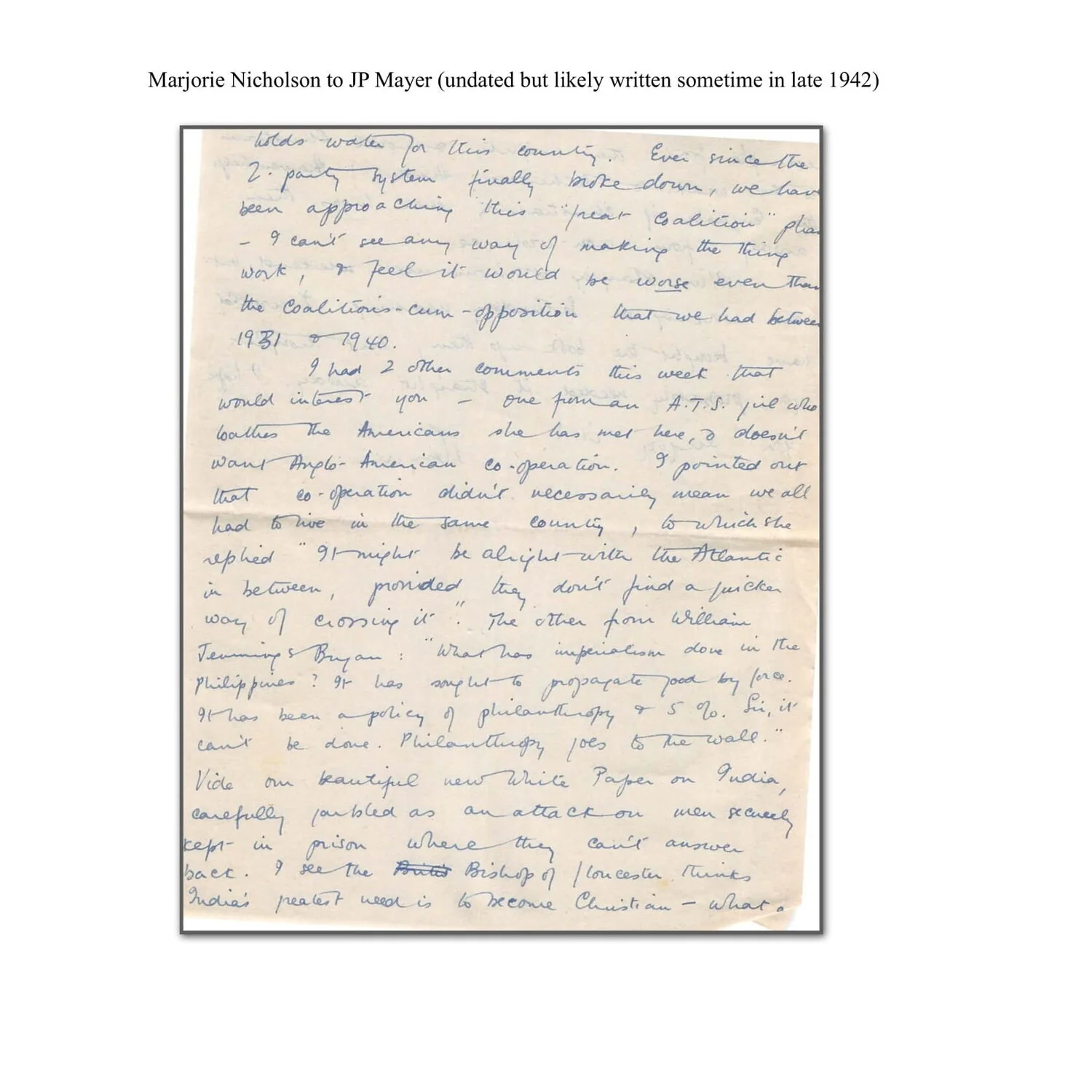

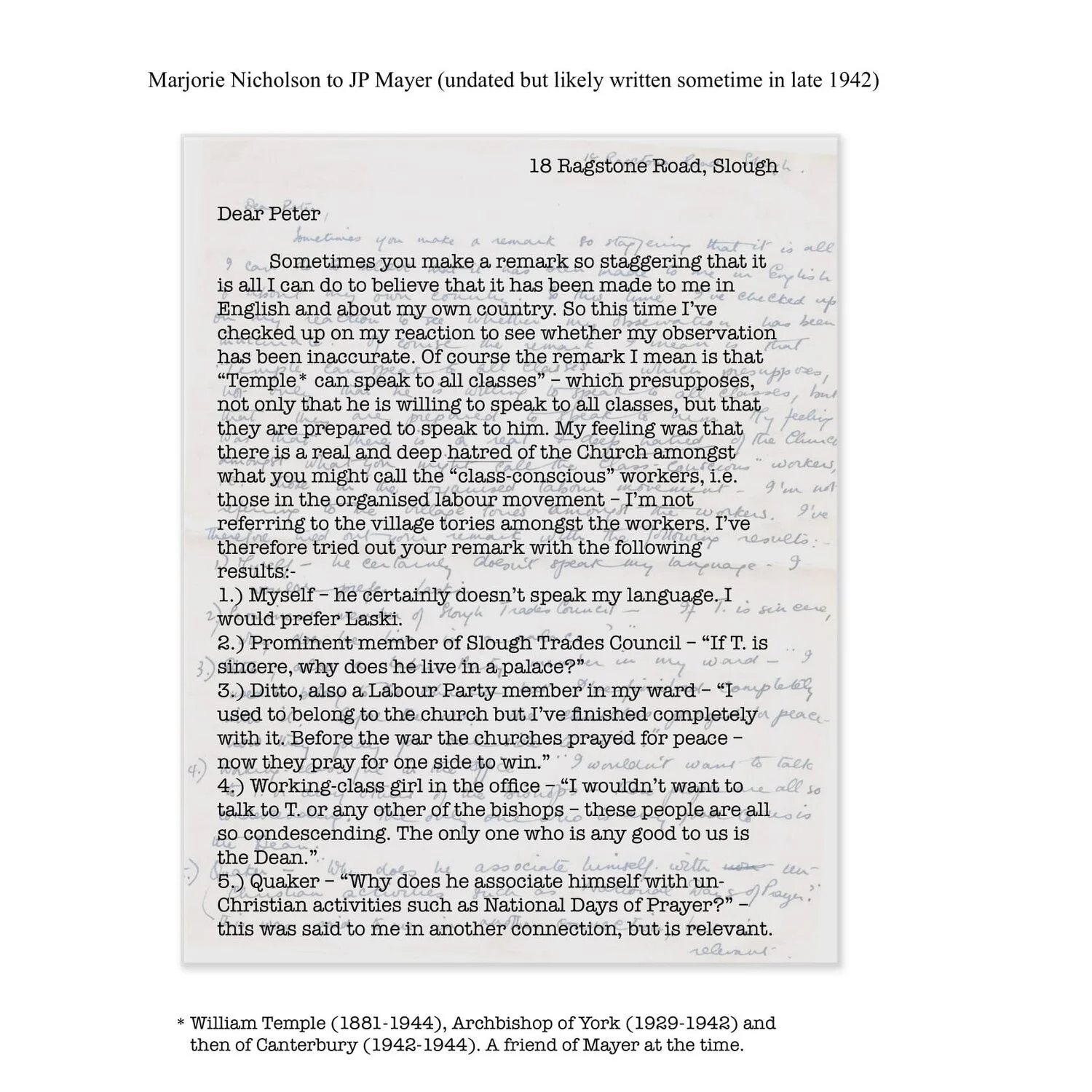

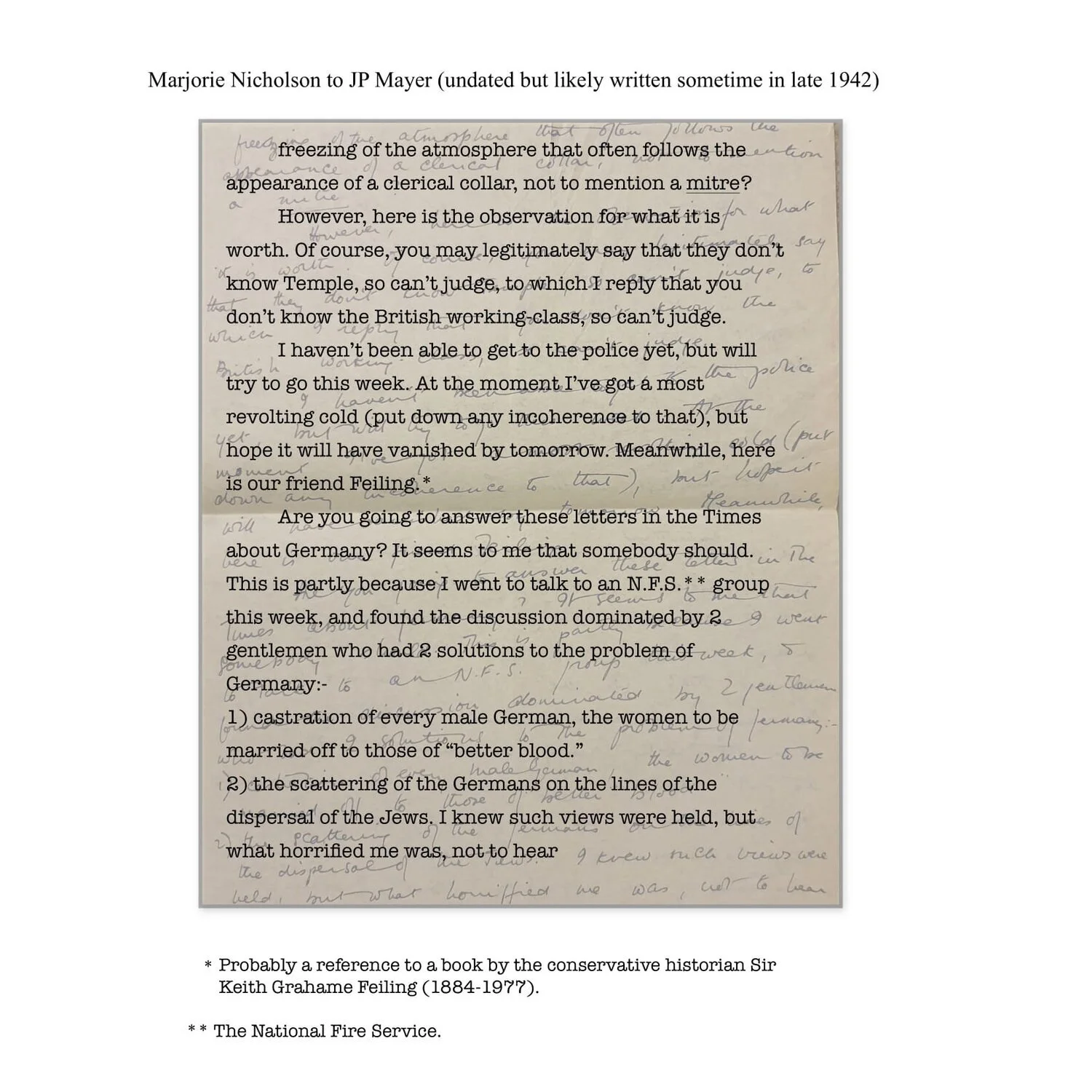

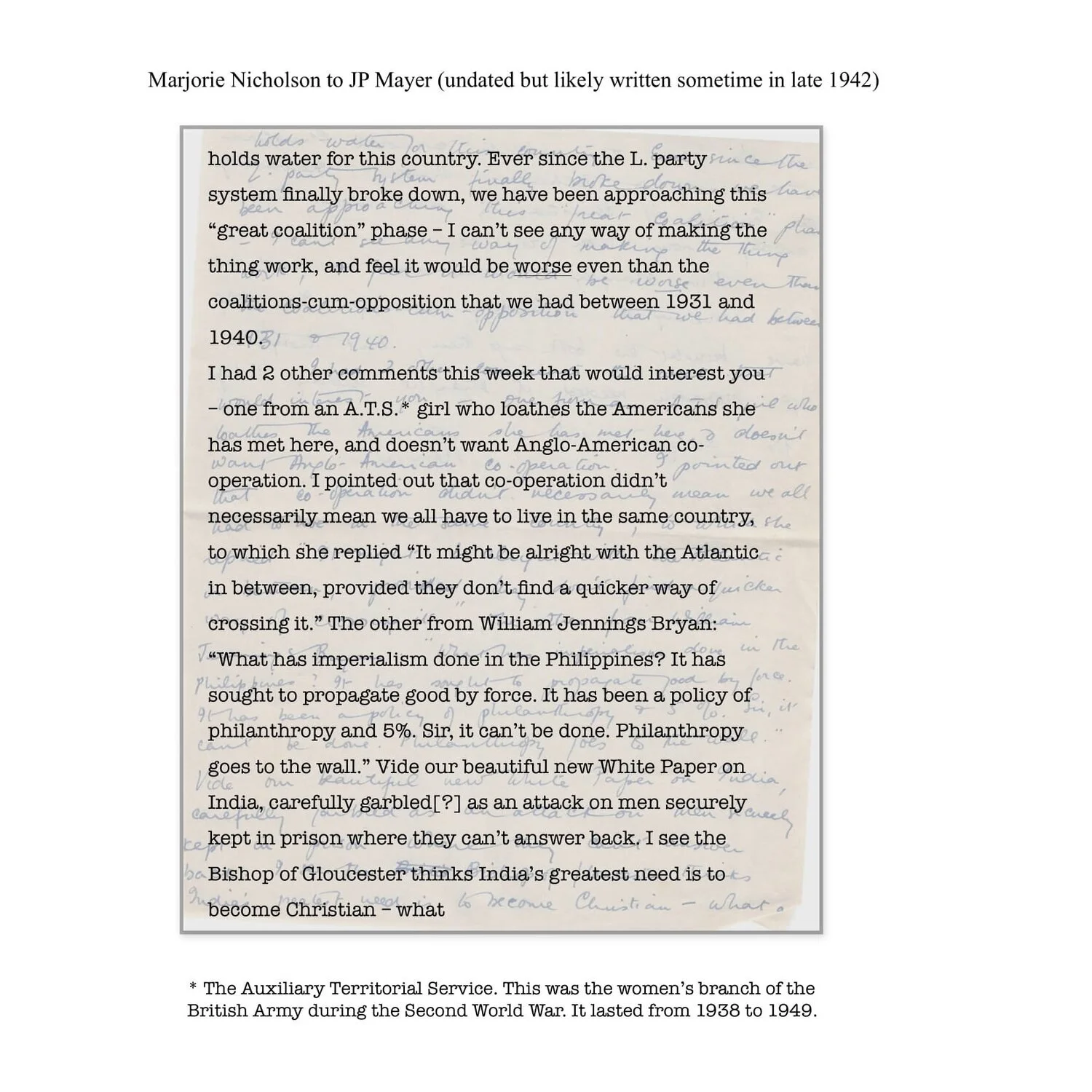

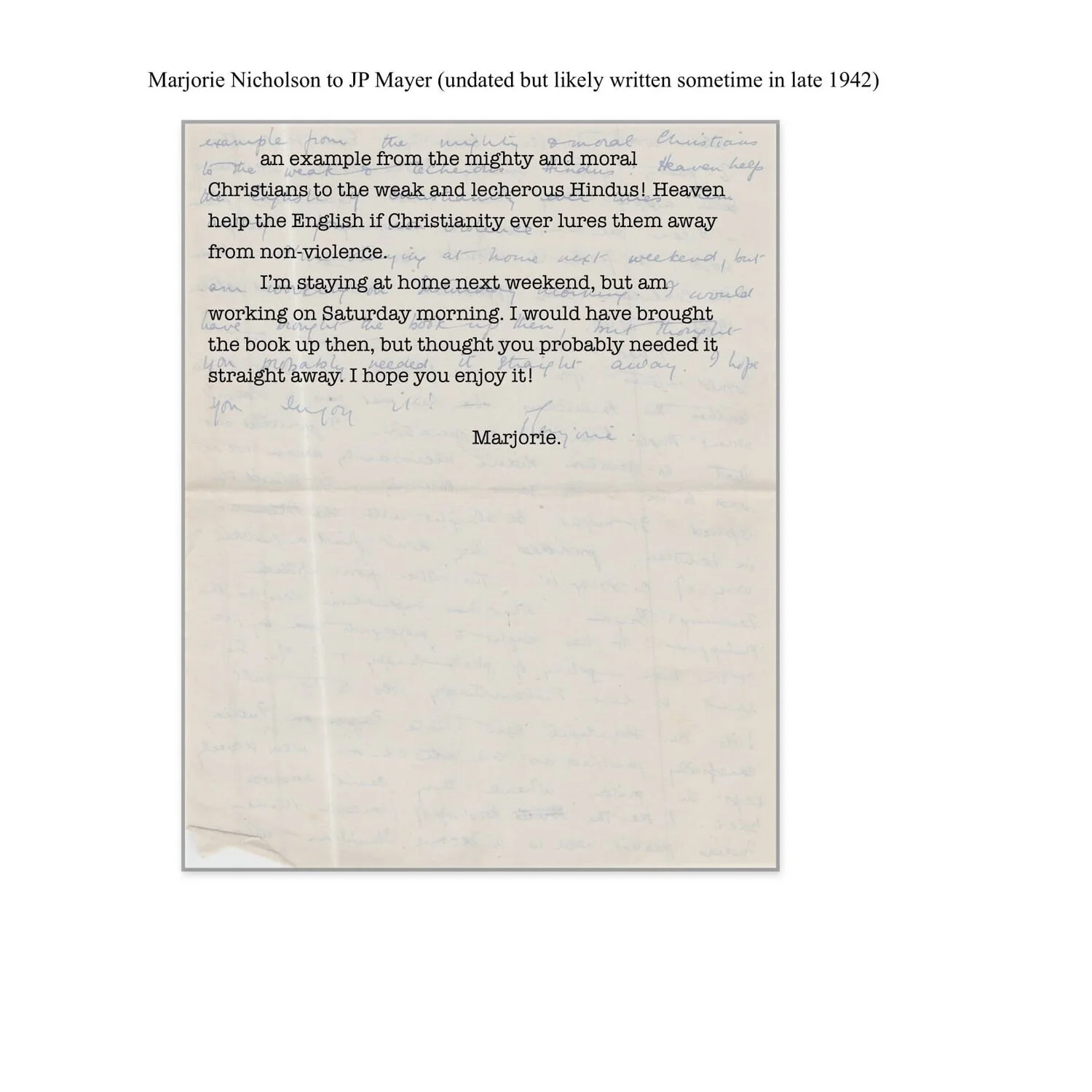

A letter from Marjorie Nicholson

Item No. 8.

Marjorie Nicholson

Marjorie Nicholson (1914-1997) was a socialist and trade unionist. The daughter of a manager of a hat factory, she won an open scholarship that enabled her to read modern history at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, and it was there that she began to question the conservative values she had grown up with. She attended meetings organized by the Oxford University Labour Club, came into contact with working-class men and women at Ruskin College, and, in 1934, avowed a commitment to socialism. “I found that all the information on which I had hitherto based such views as I had, had been incorrect”, she said in 1945 while recalling her political conversion. After graduating, she worked as a teacher at the East Ham Grammar School for Girls and then as a tutor for the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA). Following the war, she became assistant secretary for the Fabian Colonial Bureau and took the opportunity while employed there to spend a three-month sabbatical teaching adults in Nigeria. In 1950 she left the bureau to join the Commonwealth section of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) where she focused on policy development. A committed socialist both in thought and action, she stood three times as the Labour candidate for the staunchly conservative constituency of Windsor between 1945 and 1951, and was a lifelong opponent of colonialism, believing that equality should exist between races and nations as well as between individuals. When she died in 1997 at the age of 82, she was working on a history of the TUC.

JP Mayer (1903-1992) first met Nicholson in early 1942 when he began teaching for the WEA branch where she worked as the Organising Tutor. A close friendship soon formed built on mutual respect and shared intellectual interests. “Can you accept once and for all that I have the greatest respect for you as a man and a scholar, [and] that I believe your sincerity to be unimpeachable…?”, Nicholson wrote to Mayer in 1943. They did not always see eye to eye on political issues but they were always willing to engage with the other’s opinions. It was a friendship that continued for almost half a century. Forty years after they first met, Mayer was still soliciting Nicholson’s views on his written work. In the last letter from Nicholson that was found among Mayer’s papers, dated December 1987, she expressed the hope that she could meet up with Mayer and his second wife, Edna, in the spring. Nicholson continued to write warm letters to Edna after Mayer’s death in 1992.

The letter posted here, in which Nicholson savages Mayer’s claim that William Temple, the Archbishop of Canterbury, “can speak to all classes”, captures both the intimacy and the intellectual repartee characteristic of their correspondence.