J. G. A. Pocock on J. R. R. Tolkien

Item No. 10.

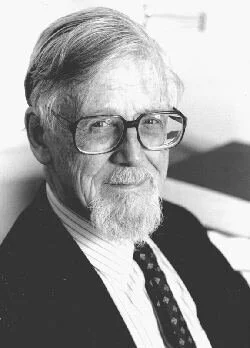

J. G. A. Pocock

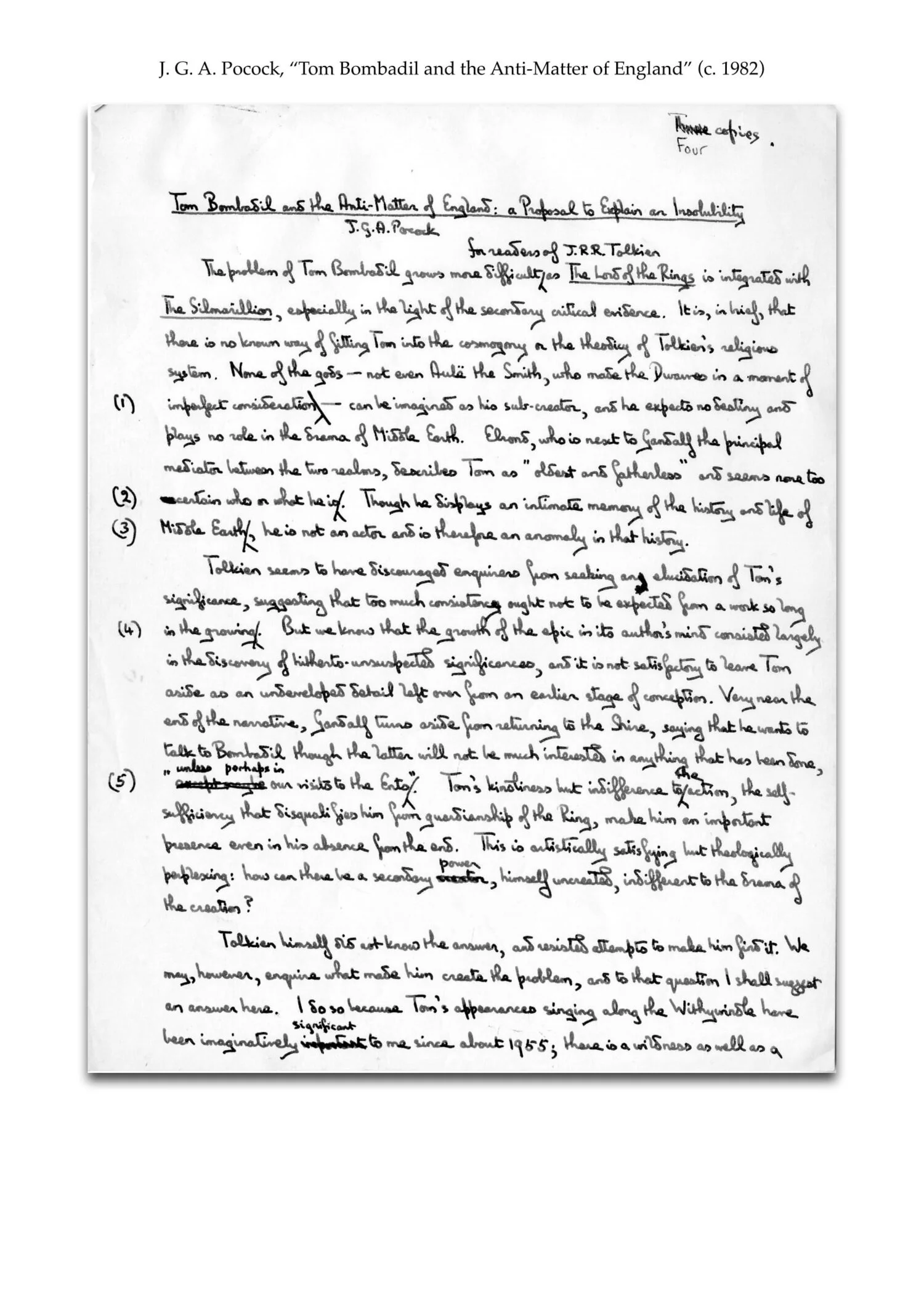

Tom Bombadil and the Anti-Matter of England: A Proposal to Explain an Insolubility

The character of Tom Bombadil is well-known to everyone familiar with the literary universe of J. R. R. Tolkien. The question of the true significance of this mysterious creature has preoccupied readers ever since he first appeared in The Fellowship of the Ring in 1954. A veritable ‘Bombadilology’ has since sprung up within the world of Tolkien fandom, dedicated to exploring the problems and conundrums raised by this enigmatic character, whose exact place in the history and narrative of Middle Earth was left oddly unexplained by Tolkien, thus raising questions about the creative consistency of his oeuvre. Among those readers whose curiosity was awoken early on by Bombadil was the historian J. G. A. Pocock, who stated - in an unpublished essay c. 1982 - that the image of Bombadil ‘singing along the Withywindle’ had been ‘imaginatively significant’ to him since 1955. In this essay - made public here for the first time - Pocock provides his own very interesting solution to the Bombadil “problem”; a solution that proposes to ‘explain an insolubility’ rather than explaining it away.

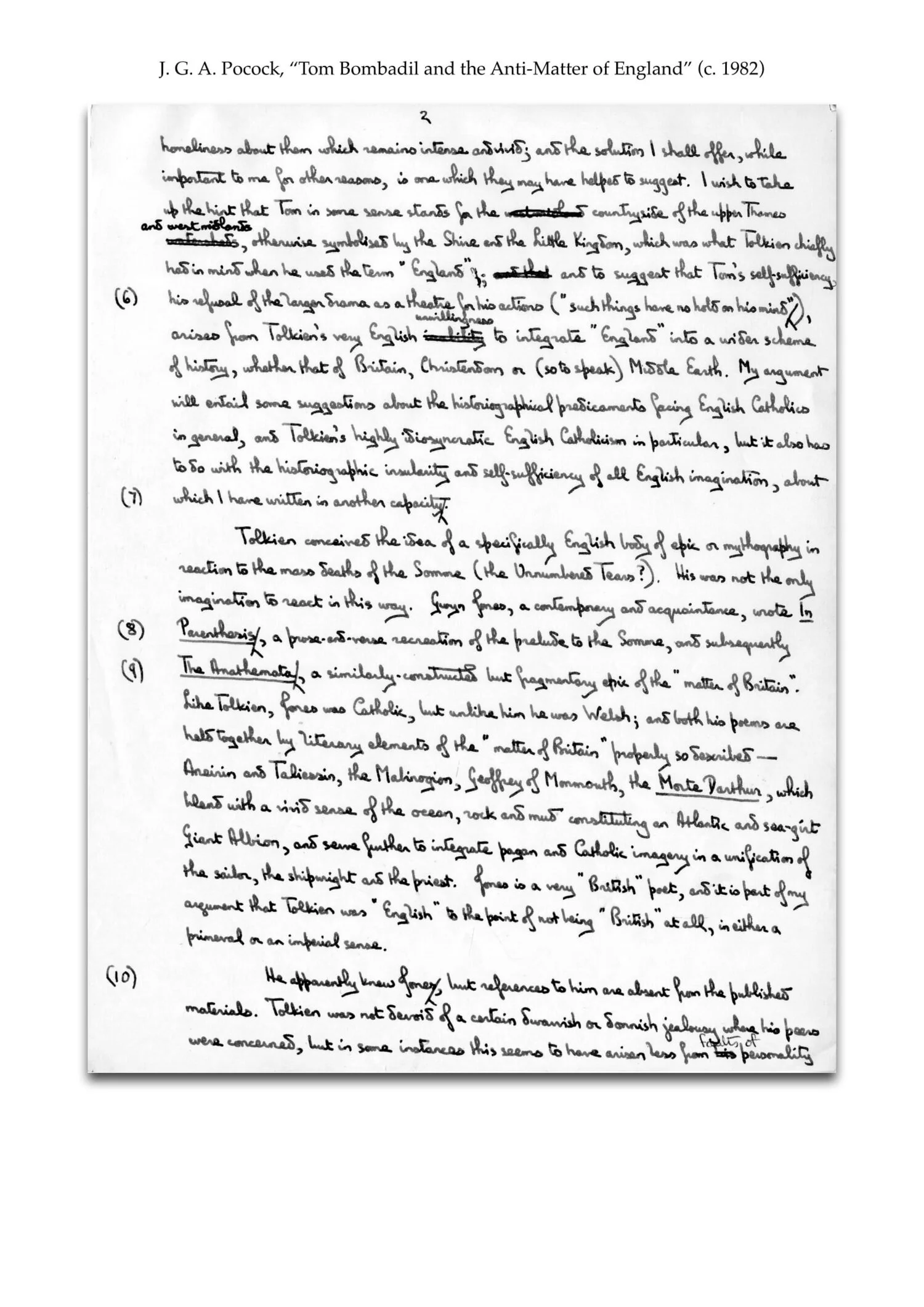

In critical dialogue with the Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, published in 1981 by Tolkien’s biographer Humphrey Carpenter, Pocock developed the idea that Bombadil in some way represents England. Not simply understood as Tolkien’s beloved English countryside, but as his imaginative point of departure which - due to its creative primacy - defies full integration into the secondary world of Middle Earth. As such, this constitutes not only an insightful reading of Tolkien, it is also a reading that clearly resonates with Pocock’s own historiographical concerns in the early 1980s and, more specifically, with his long preoccupation with the peculiarity of the ‘English Mind’ and England’s reluctant integration into larger conceptual entities such as Great Britain, Europe, Christianity and the Enlightenment. His claim that Tolkien was ‘English to the point of not being British’ could, for instance, aptly stand as an epitaph for the kind of historiography that he wished to see replaced by his revisionist quest for a properly British history; a project that began with his ‘Plea for a New Subject’ in 1974, and which received its fullest formulation in ‘The Limits and Divisions of British History: In search of the Unknown Subject’ (1982).

The ‘insolubility’ of Tom Bombadil thus becomes a token of the fact that Tolkien’s imagination was equally embedded in the same ‘historiographic insularity and self-sufficiency’ that characterised ‘all English imagination’ in Pocock’s mind, and which he had, as he wrote, ‘written about in another capacity’. Pocock’s reference here is to his latest revisionist project, but as he himself relates, his thinking about Bombadil goes back to 1955, and it is obvious that the germ of his interpretation of Tolkien is to be found in the content of his first book, The Ancient Constitution and The Feudal Law (1957), whose completion followed closely after his first encounter with Bombadil. This book, which he developed from his Cambridge PhD, was an attempt to explain the slow emergence of historicism in English political thought out of a common law mindset characterised by the complete absence of any sense of its own historicity. Exemplified by the 16th century lawyer Sir Edward Coke, the Common Law mode of thinking was rooted in ideas of an unchanging customary law whose authority derived from its unbroken continuity; from its origin in ”time immemorial”. As such it was entirely self-contained and self-sufficient— not unlike Tom Bombadil - allowing of no relation or comparison with other legal systems. In stark contrast, legal theorists in France and Scotland, notably François Hotman and Sir James Craig, already thought comparatively and historically about law, using the techniques developed by Renaissance humanists in their effort to understand the Graeco-Roman past. It was not until the 17th century that legal antiquarians in England realised that the tenure system of England only made sense against the background of a feudal law that had been introduced at some specific point in history. Once this discovery was made and explored - by Selden, Spelman, Hale and Brady - the possibility of integrating England into a larger British and European narrative became a reality, and when James Harrington connected these feudal tenures to their material context, developing an entirely historical explanation of the causes of the English Civil War, the emergence of an integrated comparative perspective on English law was complete. Or was it? As Pocock showed in the final chapter, the idea of an Ancient Constitution persisted as an aspect of English political thought, informing the debate around the Revolution in 1688, and receiving its most sophisticated formulation in Edmund Burke’s defence of the Revolution Settlement against the supporters of the French Revolution. England was, in this regard, still outside the European narrative. But this failure of integration - just as with Tolkien and Bombadil - was not a failure of the imagination. It was a constitutive, imaginative resistance to any full participation in the plot. In other words, it amounted to a defining feature of England which, according to Pocock, could be detected even as far away as the Old Forest of Middle Earth.

- L. Andersen

The Institute thanks J. G. A. Pocock for permission to publish this essay

and Simon J. Cook for his valuable insights.