The Freyberger Letter

Item No. 9.

Helene Demuth

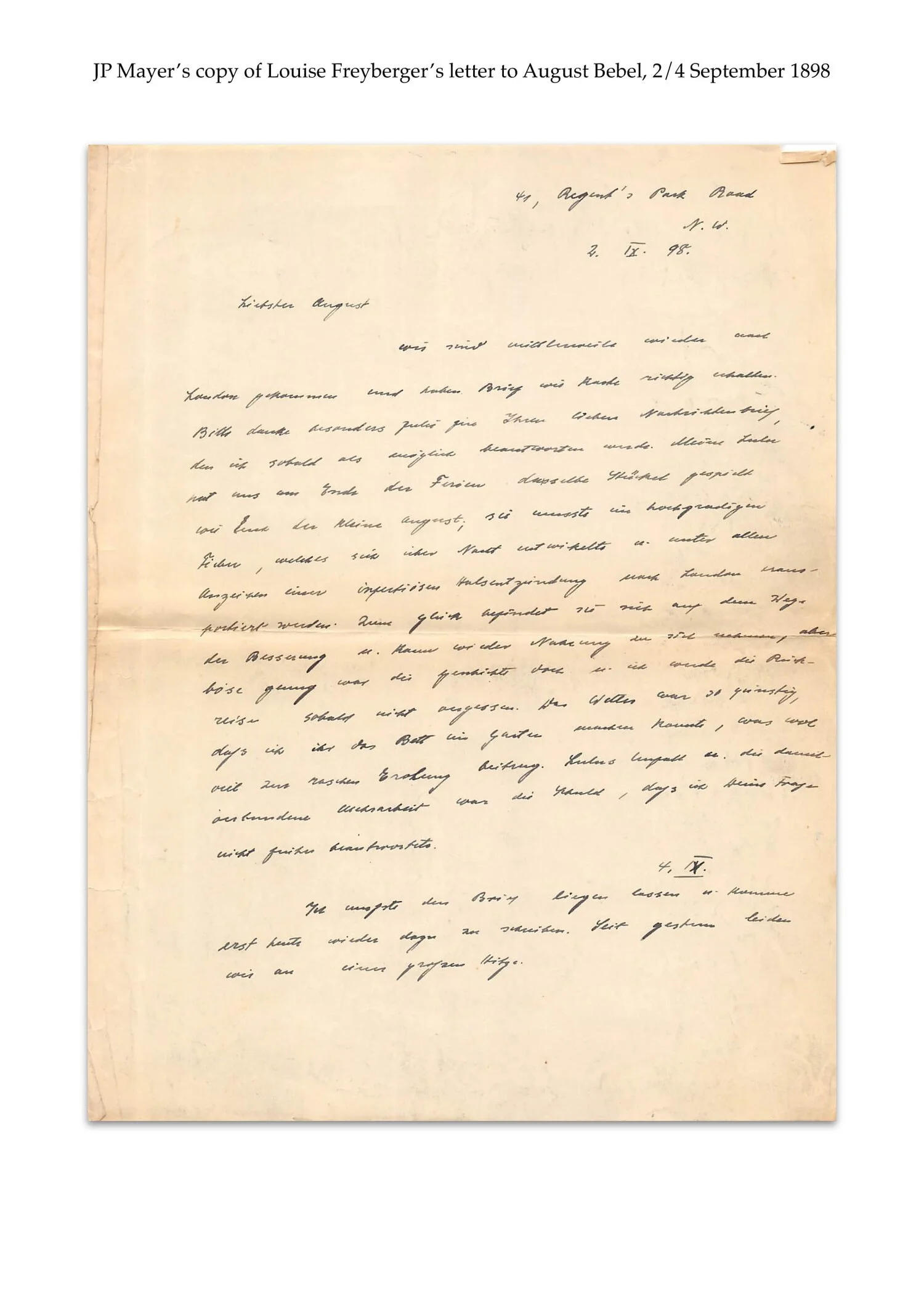

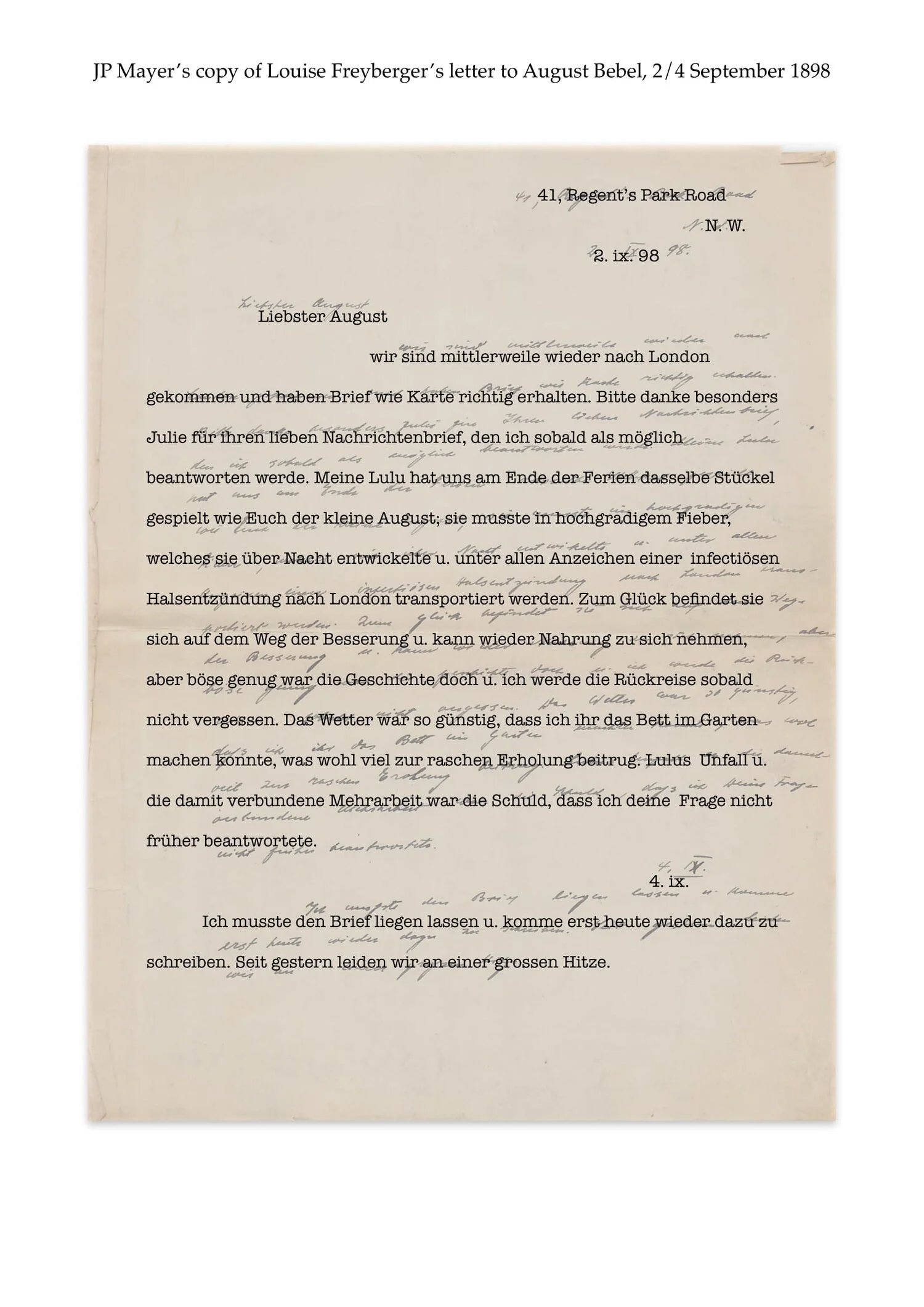

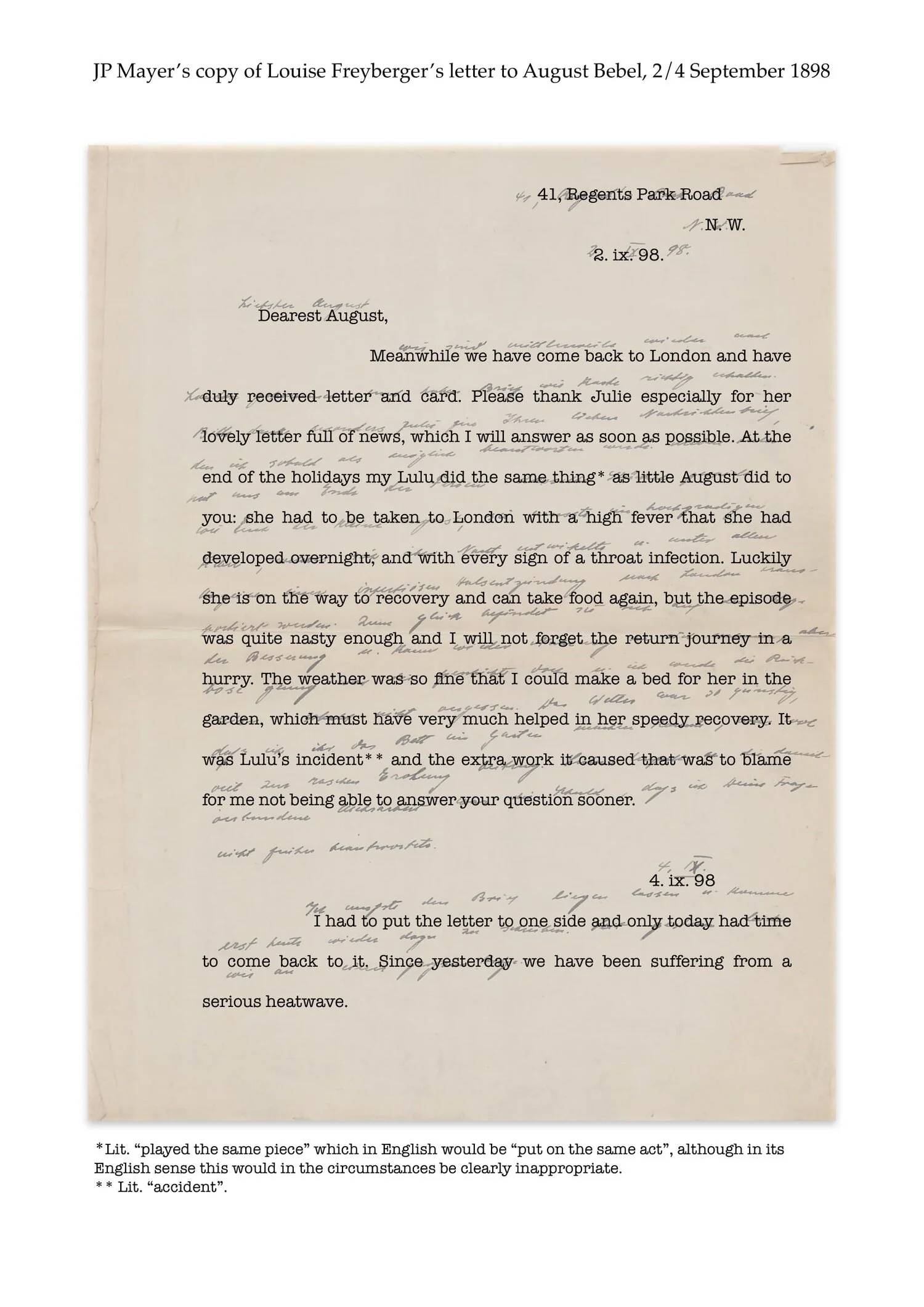

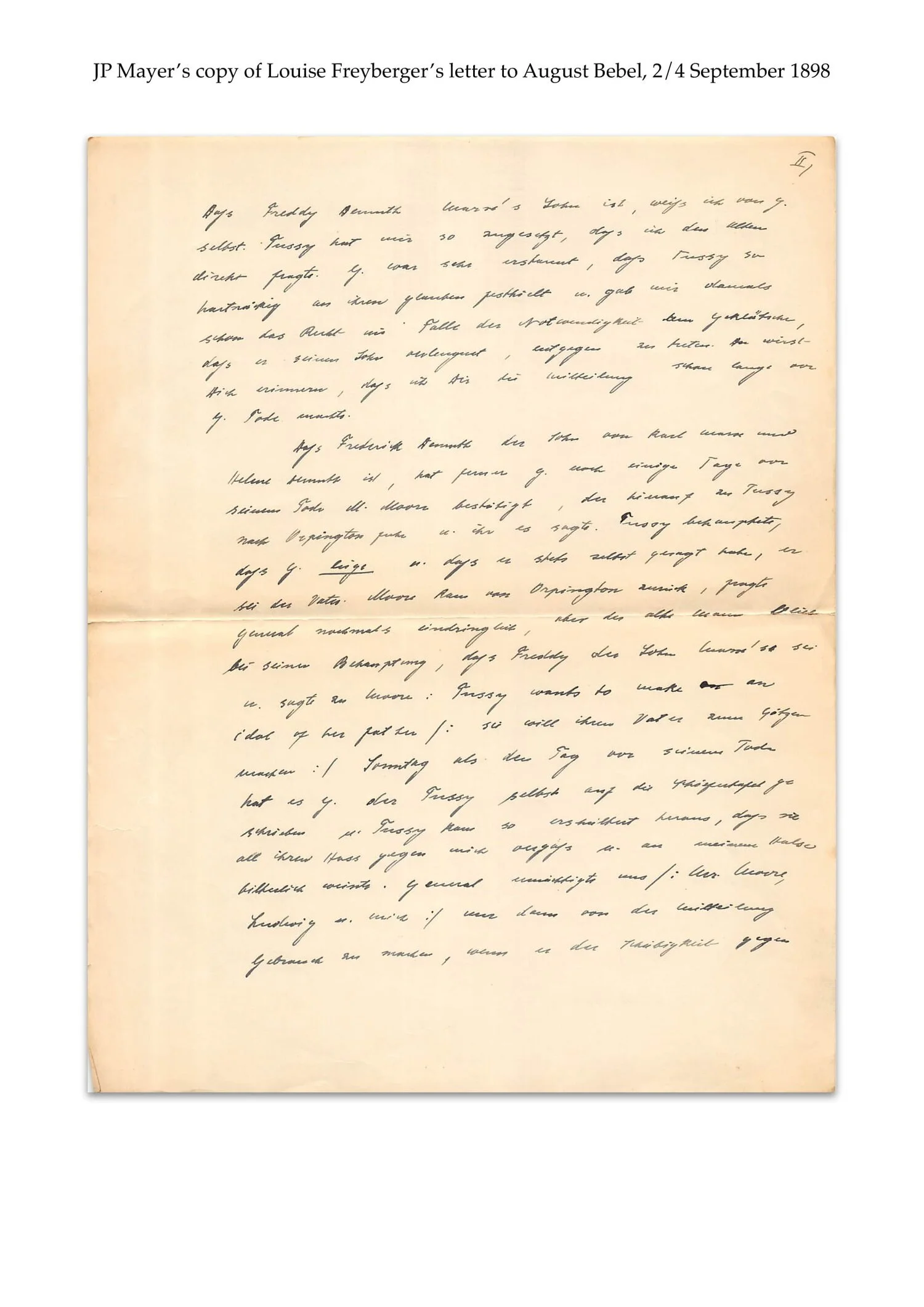

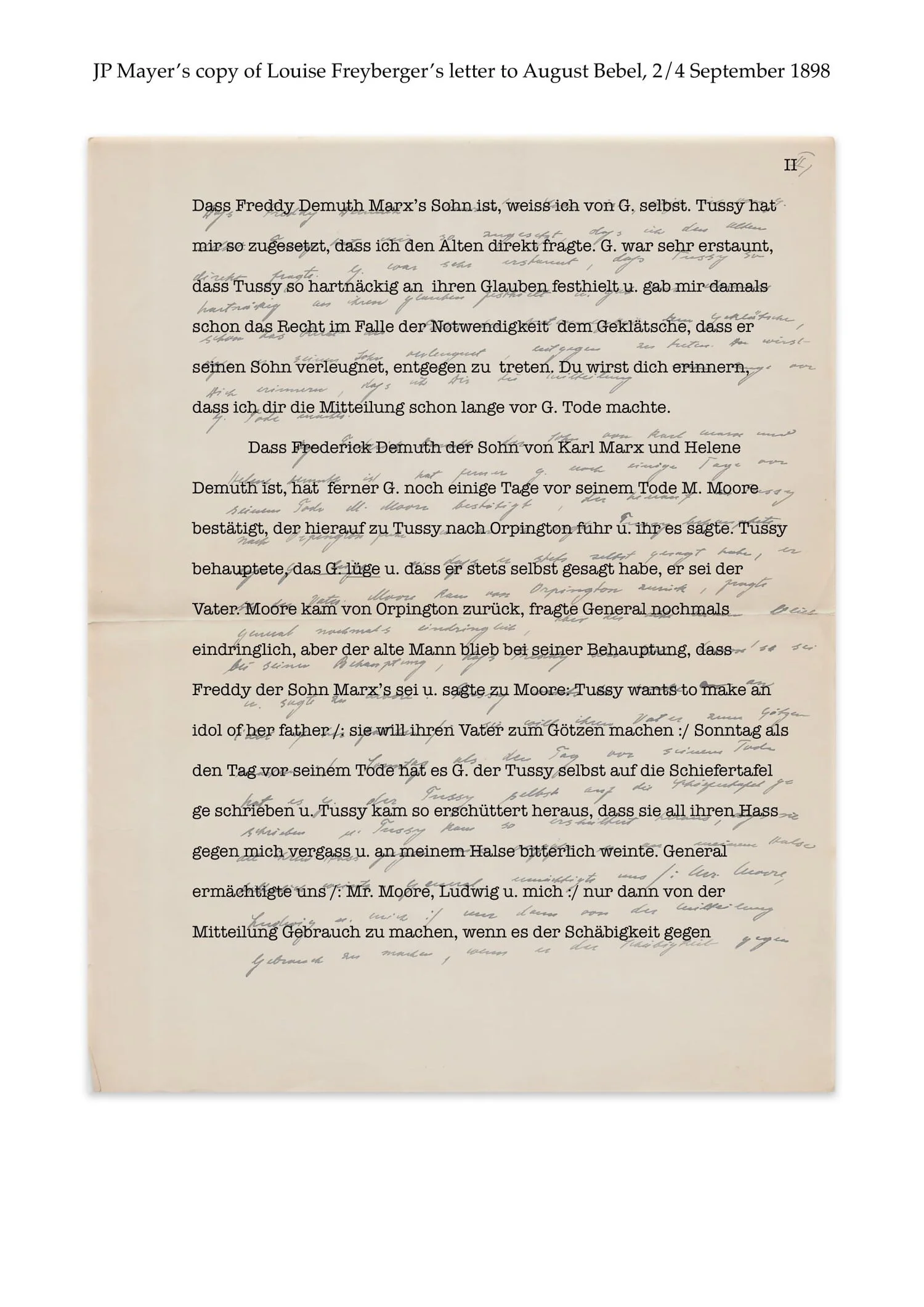

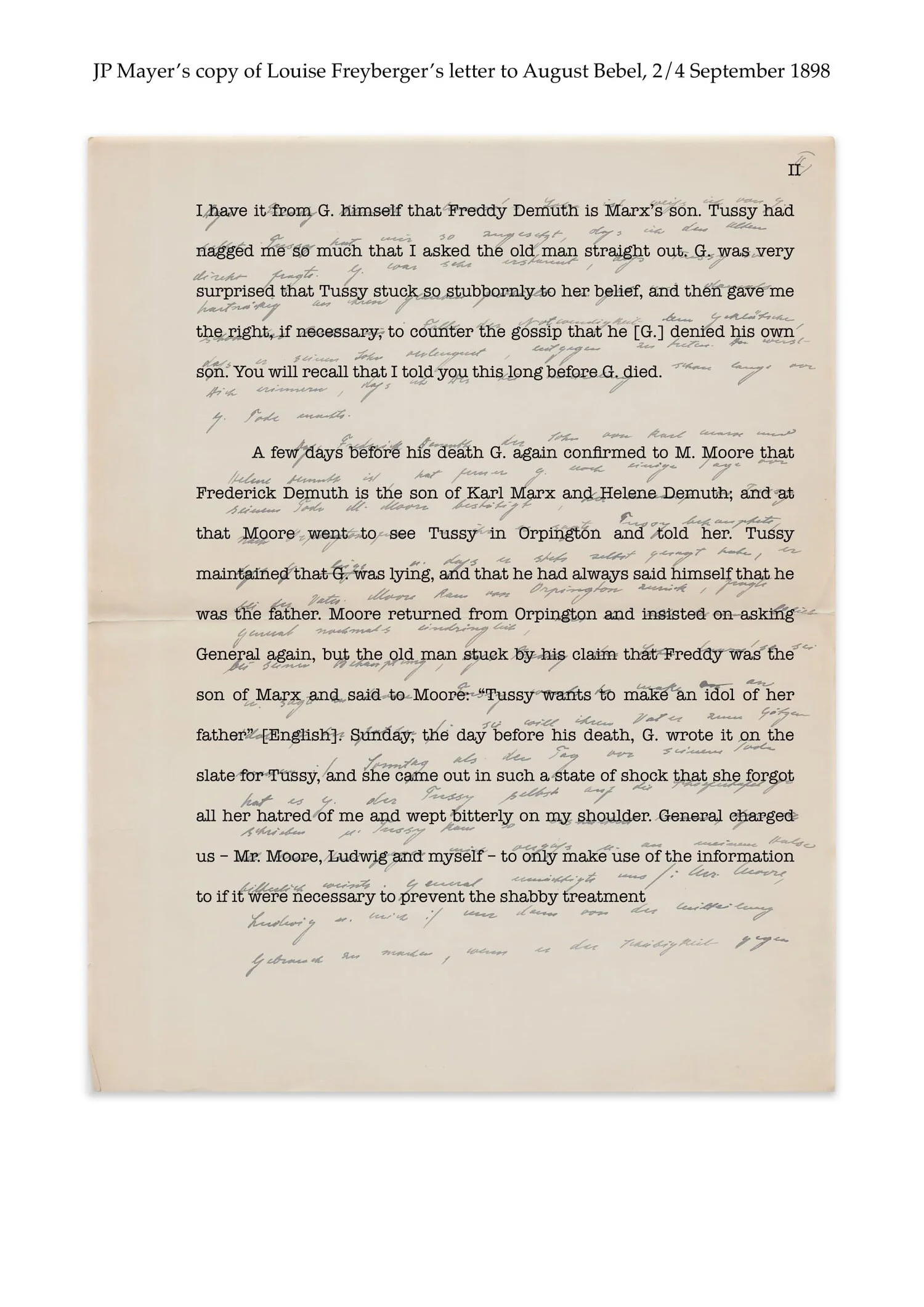

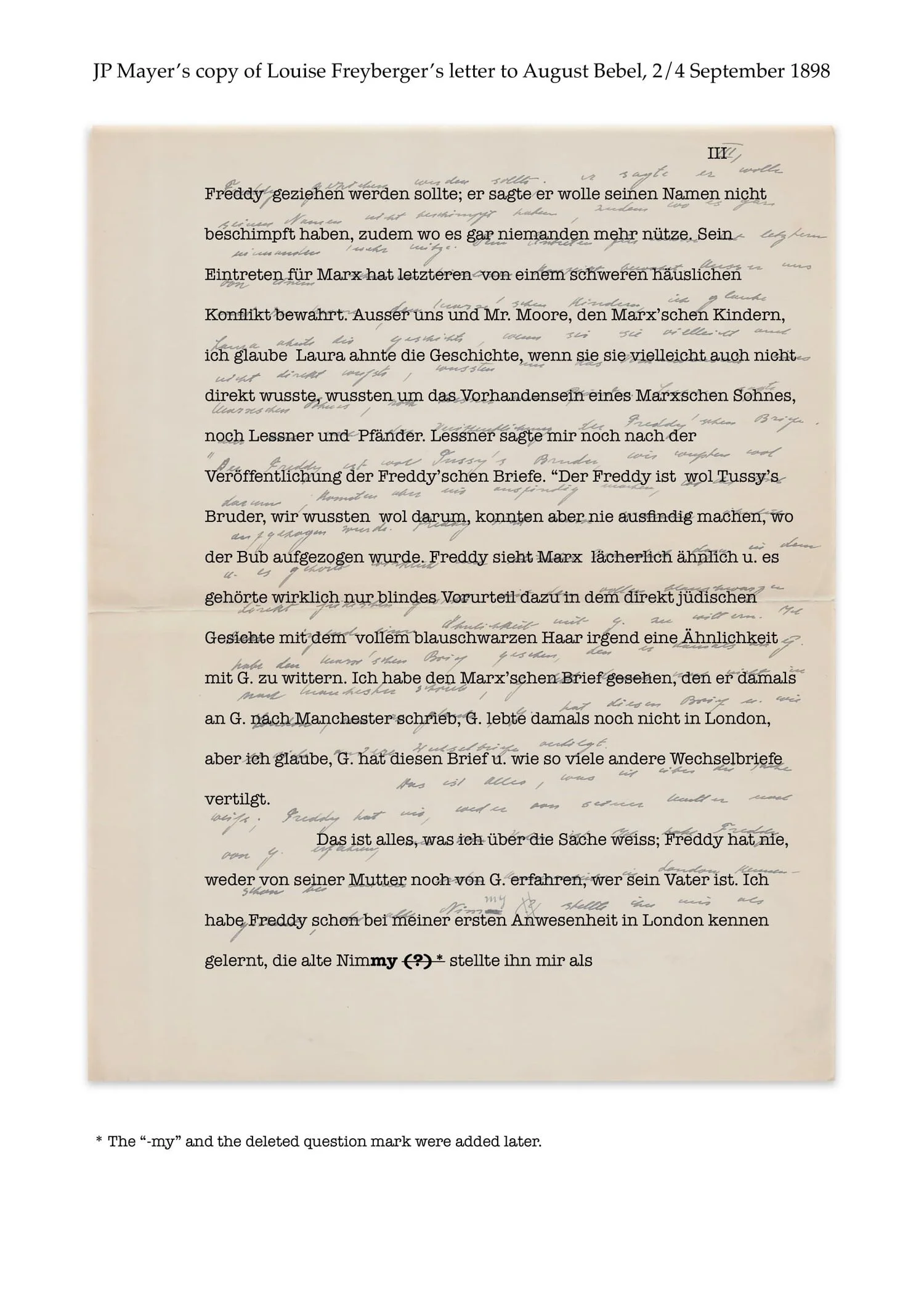

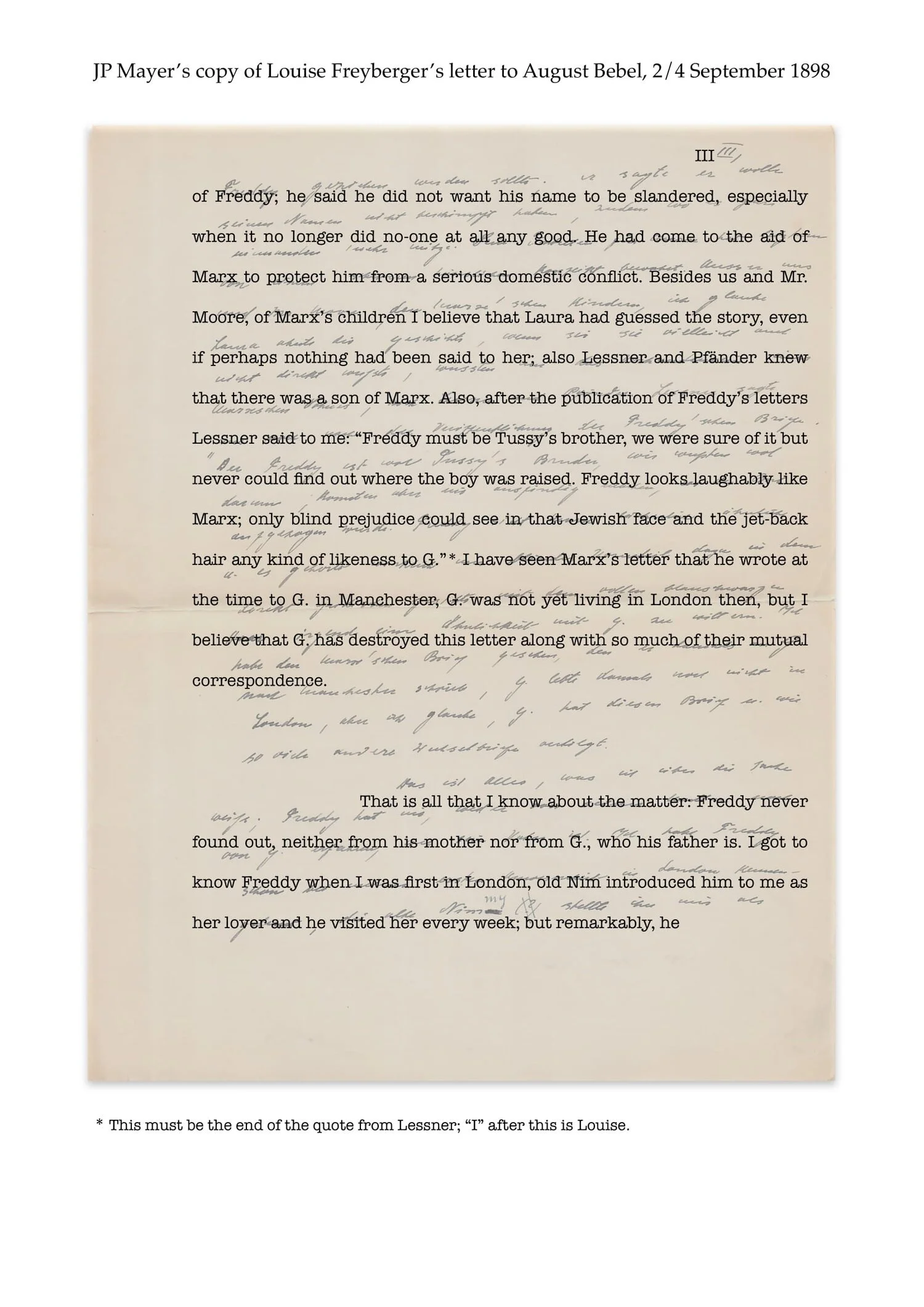

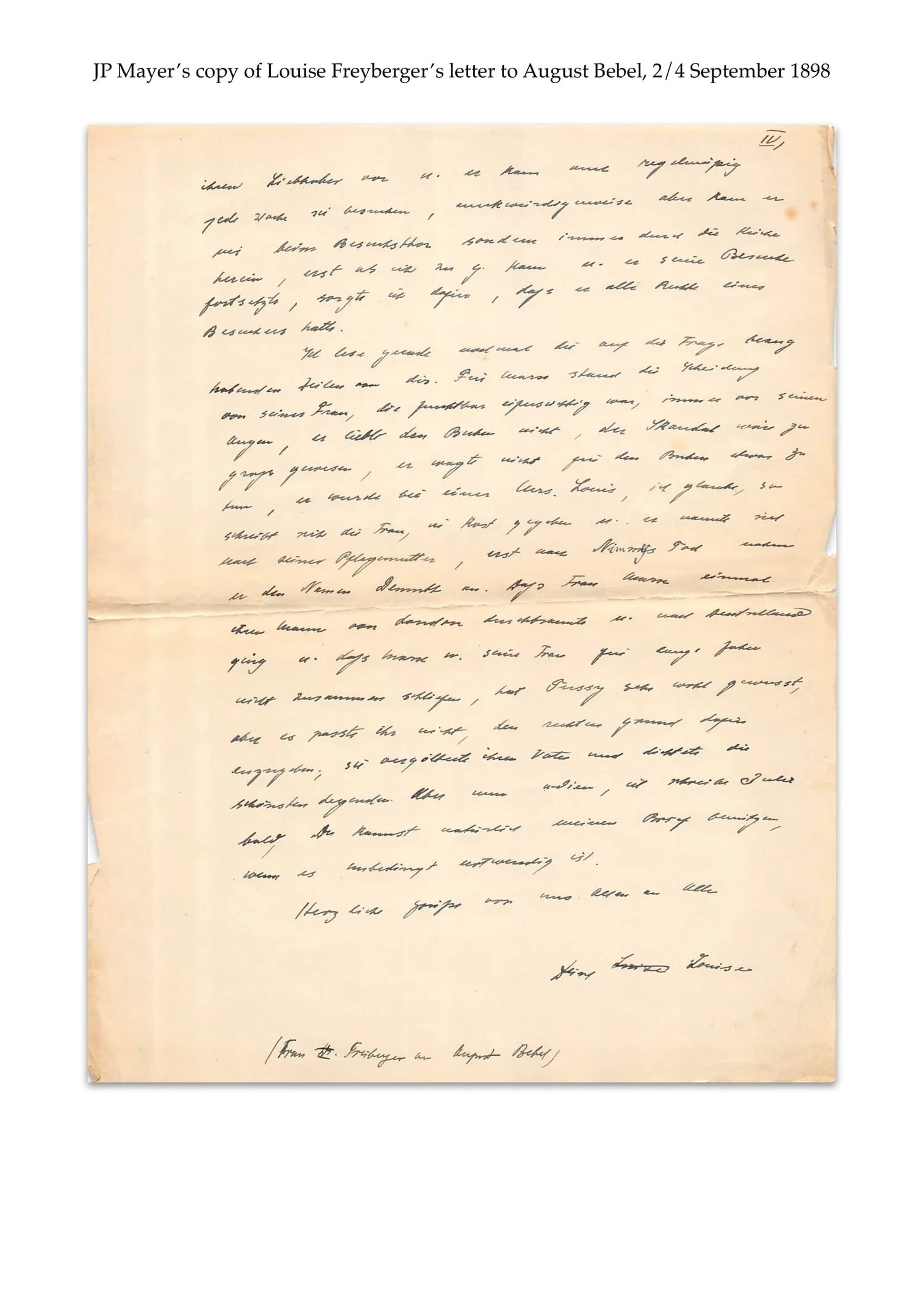

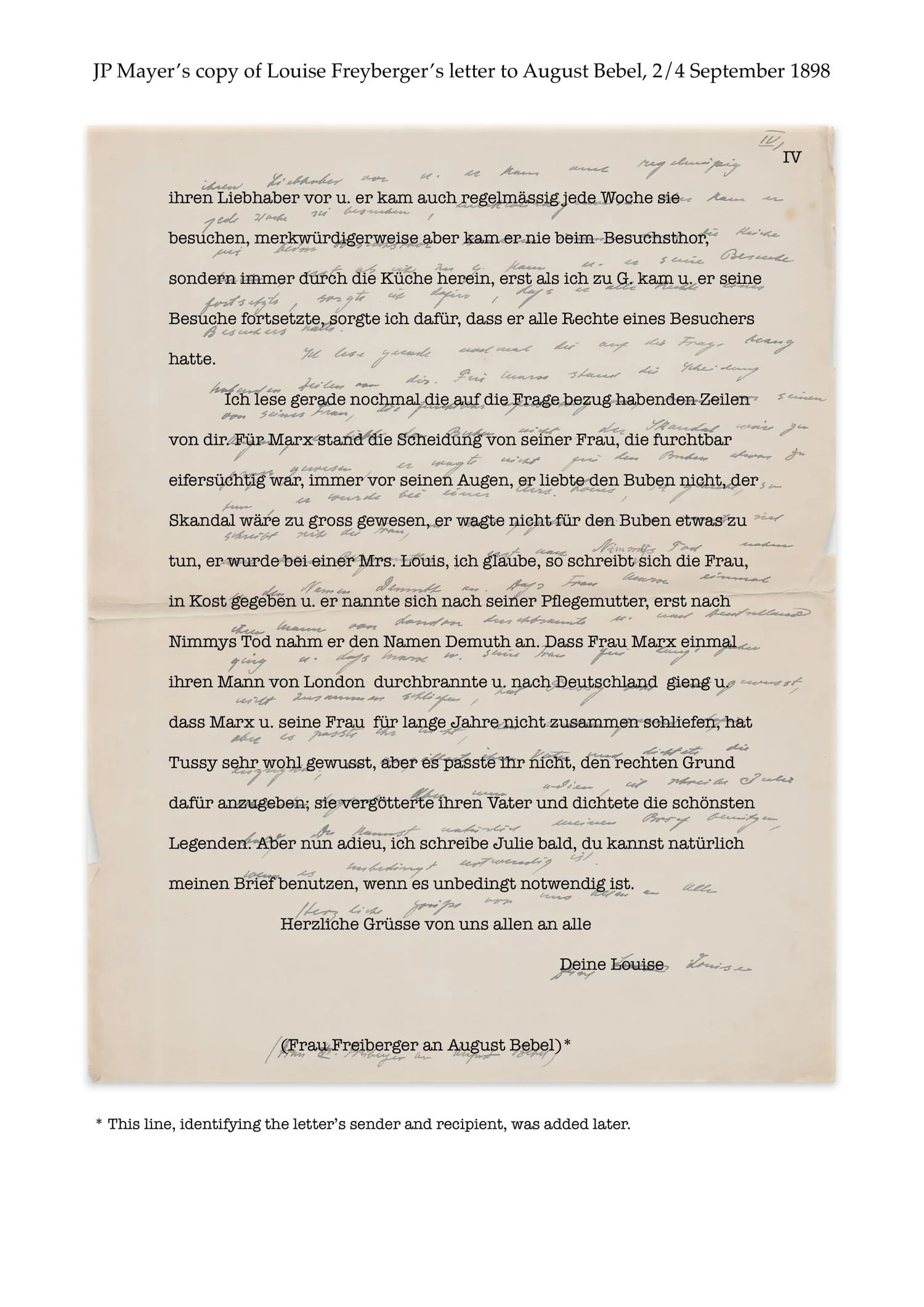

In his 1962 biography of Marx, Werner Blumenberg, who at the time was head of the German department of the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam, quoted excerpts from a letter he had discovered in the IISH’s archives which revealed that Marx had fathered an illegitimate son. The letter, dated 2 and 4 September 1898, was written by Louise Freyberger née Strasser, Engels’s former secretary and the first wife of Karl Kautsky, to August Bebel, the chairman of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, and told an improbably melodramatic tale of a deathbed confession by Engels that Frederick Demuth, who had been born out of wedlock to Marx’s housemaid Helene Demuth in 1851, was in fact Marx’s own son.

For the next few decades, historians and biographers debated the veracity of the story. Some were convinced that the leaders of the socialist circles that formed around Marx had suppressed the salacious truth to preserve the good name of their movement’s founder. Others felt sure the tale recounted in the letter was Frau Freyberger’s own malicious fabrication. A few scholars dismissed the letter as a forgery, noting that the document Blumenberg had uncovered was an unsigned typed copy of a supposedly lost original. It was only in 1994, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, that some new documents came to light which provided strong evidence that Freyberger had indeed written such a letter.

Frederick Demuth

For one scholar at least, Blumenberg’s announcement of the existence of the letter did not come as a surprise. In a review of Blumenberg’s biography that appeared in the September 1963 issue of Geist und Tat, the Tocqueville scholar Jacob-Peter Mayer (1903-1992) claimed that he had seen the letter in the early 1930s and had even shown it to Eduard Bernstein, who had dismissed Freyberger’s revelation as a fiction. If Marx’s late twentieth-century biographers had noticed Mayer’s review, then perhaps the accusations that the letter was a forgery might never have arisen.

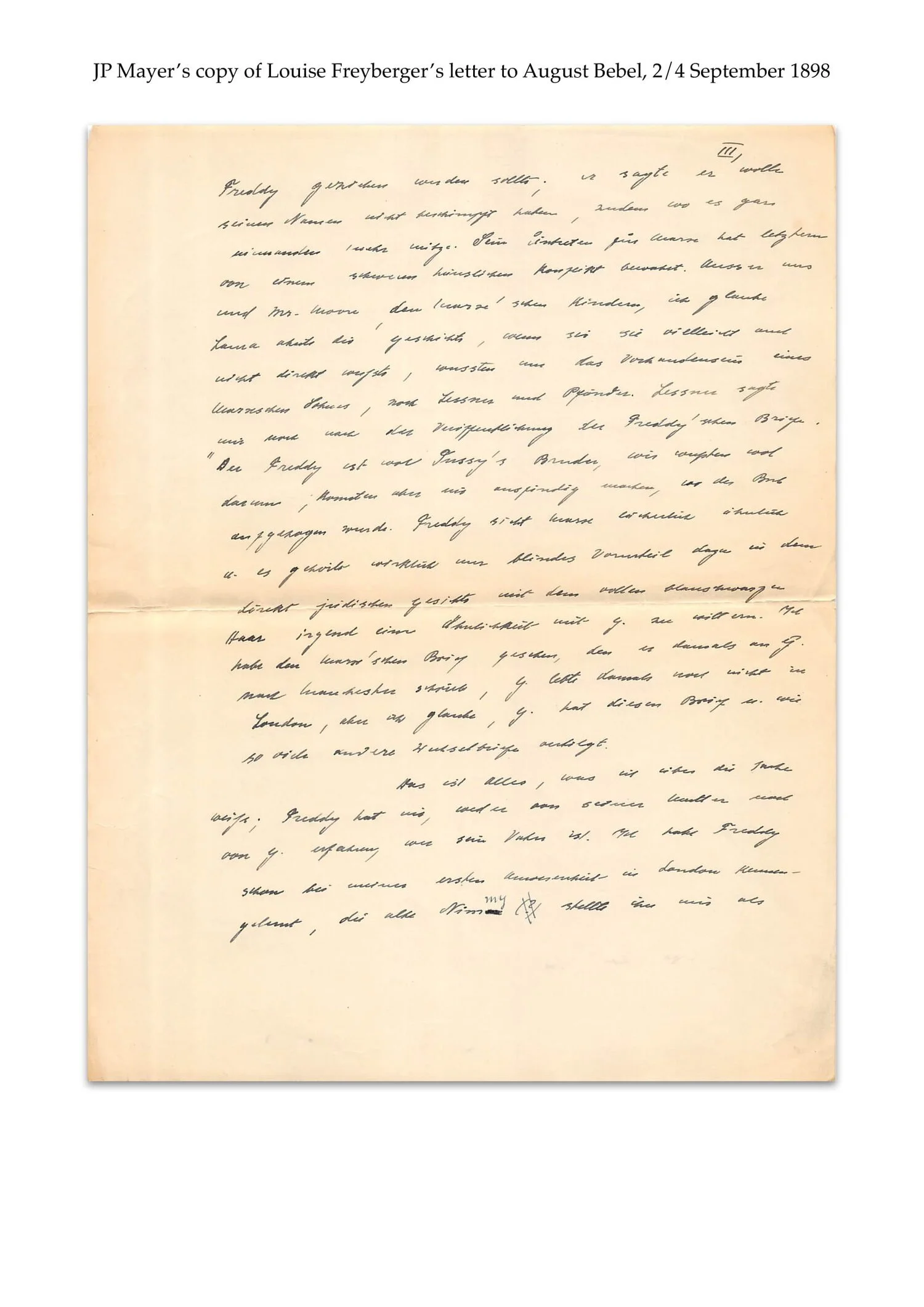

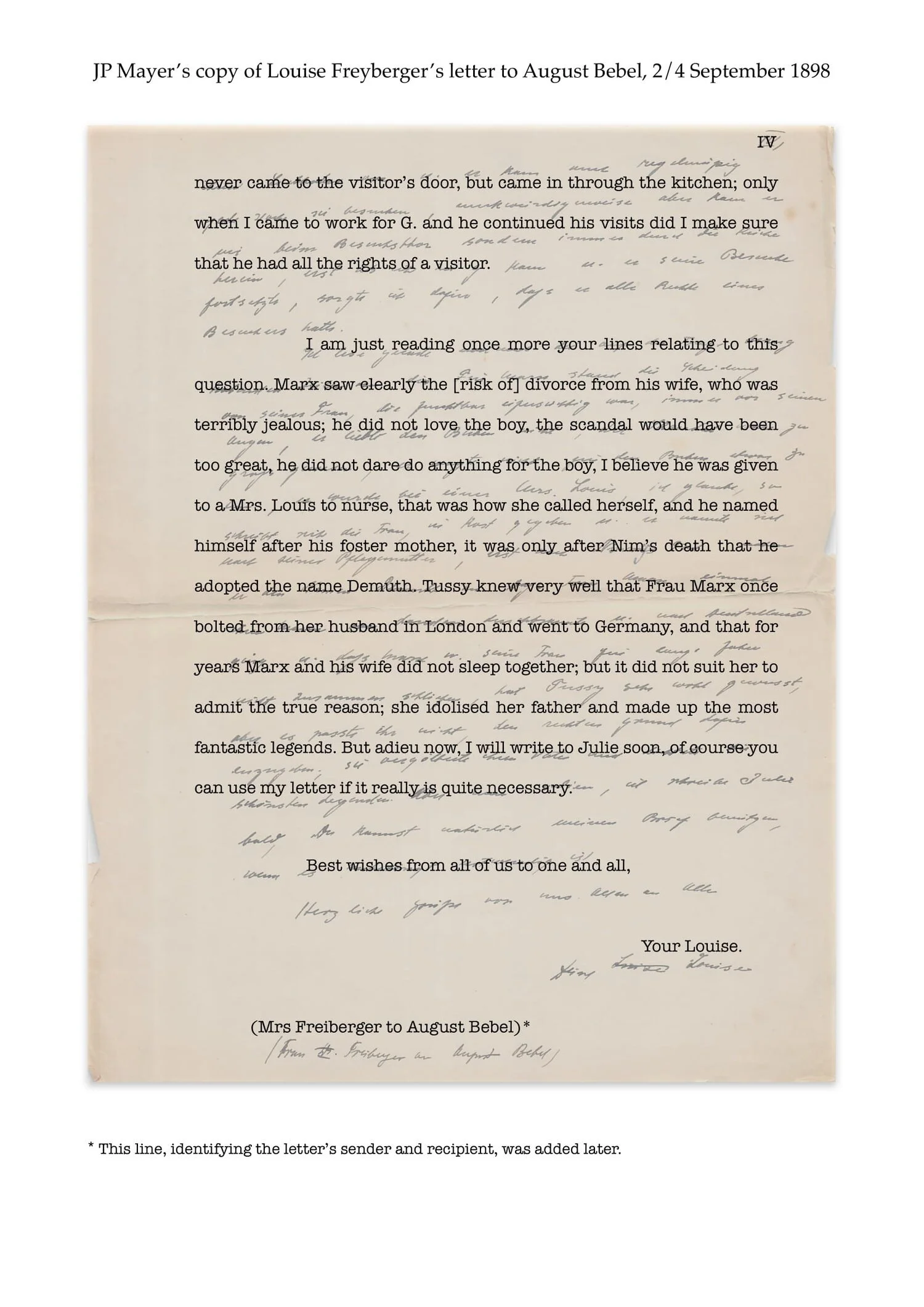

A copy of the letter written in his own hand was found recently among Mayer’s papers, which the Institute of Intellectual History at St Andrews acquired in 2018. Given that the IISH typescript is the only known copy of the original letter to have ever existed, the obvious supposition to make is that Mayer produced his copy by transcribing the IISH letter. However, though the two versions are largely identical, there are some minor differences. Mayer’s version has several extra commas, fewer paragraph breaks, some alternative spellings, and one differently transcribed word. Furthermore, there is no evidence among his papers that Mayer ever visited Amsterdam, let alone the IISH.

Another theory that explains how Mayer produced his version is that he copied it, not from the typed letter in Amsterdam, but from the original letter. Such a theory is consistent, of course, with Mayer’s claim that he had seen the letter in the early ’30s, a time when he was working in Berlin as a researcher in the archives of the SDP where the original letter was probably located. If this is the case, then Mayer’s copy of the letter, which we post here along with a transcription and a translation, may not only be an additional copy to the IISH version but may also predate it. On the question of the letter’s veracity, Mayer was unequivocal: “I myself”, he wrote in his 1963 review, “have no doubt about the facts of the case, for the inner evidence of Frau Freyberger’s letter is a poignant truth. Here, as in other human relationships, Marx proved to be undependable…. Did his father not write to him, ‘Is your heart in accord with your head, with your talents?’”

Note: For a more detailed version of the above argument see Peter Madill’s article in The History of European Ideas (47)